“In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

― Winston S. Churchill

It’s not a coincidence that among the English authors who gathered at Wellington House in London on 2 September 1914 to invent the tales that would persuade 886,000 Britons to die horribly pointless deaths in the trenches and on the battlefields of the First World War, more than a representative few had played cricket in J.M Barrie’s amateur cricket team, the Allahakbarries, in the 1890s.

It’s even less of a coincidence that the most influential among them, notably Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Rider Haggard, and John Buchan, had earned their agitprop spurs in the Boer War of 1899 to 1902.

Both of them provided field days, that quaint English phrase that signifies “…an opportunity for action or success, especially at the expense of others.”

On the village green of Broadway, in the Cotswolds, they learned that it wasn’t whether you won or lost but how you played the game.

On the dusty veld of the Transvaal they learned that it wasn’t whether you won or lost but how you wrote the story.

I read H.W. Wilson’s With the Flag to Pretoria alongside Conan Doyle’s The Great Boer War and Denys Reitz’s Commando: A Boer Journal of The Boer War, all three of them written before the ink had dried on the Treaty of Vereeniging. So they read more like reportage than recollection. Events are recorded and processed on the hoof, literally in Reitz’s case. The facts of the war are interpreted, evaluated, and judged as they occur—unmediated by the opinions of others or by the reflection that time and distance would naturally bring. In this way they are significantly more representative of the mood of the time than later histories: not because they give us the unmediated raw data of first-hand experience, although there’s plenty of this in Commando, but precisely because they are mediated by the specific and individual minds of their authors. So we know exactly what they were thinking, and how they were thinking.

I’m not intending to rehearse the war itself, nor the pronounced or unpronounced reasons for it, nor the way it played out. Nor am I going to delve into the consequences of it, even though they were so profound and so far-reaching you can still read them in the politics of South Africa today, as well as (if you dig deep enough) in the runes of contemporary geopolitics.

No, it’s what and how Wilson and Conan Doyle were thinking that interests me, for the simple reason that for most of my life I thought the way they did.

With the Flag to Pretoria and The Great Boer War are clearly written with the appetites of the British reading public in mind, as romances in the manner of Robert Louis Stevenson, but now with the moral intent foremost, thinly disguised as historical or political analysis, to make the same point that was being made over and over again by the popular English novels of the late 19th century, that the point of life’s hardships is to teach you a lesson. The lesson being to know your place and be grateful for small mercies.

It’s difficult to say which of them is more specious or more pernicious.

In his introduction, Wilson writes:

“The great principle upon which the British Empire has been built up is that all men are equal before the law, and that all civilised races stand upon precisely the same footing. As we profoundly believe, not that we English are the favoured people of God, but that so long as we are faithful to the noblest call of duty and to the higher instincts which are in us as a race, we are helping the cause of progress, which is the cause of God, we know that, whatever checks, whatever vicissitudes, whatever disappointments may befall, we march to victory. Our cause is the cause of liberty and of the right.”

Even if we excuse his inexcusable but perfectly natural assumption that by “civilised races” he clearly means “white races”, Wilson’s introduction raises more than one or two questions. Like what they were doing there in the first place, and whose liberty were they talking about in the second. Then maybe the even trickier question of what he means by “right”.

But there is something more honest in his astonishing disingenuousness than in the pains Conan Doyle takes to spell out Britain’s motive as something other than an imperial greed for gold:

“There was a vague but widespread feeling that perhaps the capitalists were engineering the situation for their own ends. It is difficult to imagine how a state of unrest and insecurity, to say nothing of a state of war, can ever be to the advantage of capital…

“The suspicion, however, did exist among those who like to avoid the obvious and magnify the remote, and throughout the negotiations the hand of Great Britain was weakened, as her adversary had doubtless calculated that it would be, by an earnest but fussy and faddy minority. Idealism and a morbid, restless conscientiousness are two of the most dangerous evils from which a modern progressive State has to suffer.”

From a 21st century perspective, Wilson’s “liberty” and “right” are more comprehensible, more palatable, and certainly less disingenuous, than Conan Doyle’s fatuous dismissal of the possibility that war could “ever be to the advantage of capital”.

The estimated total cost of the war to the British government was £211,156,000, equivalent to £202,000,000,000, or a fifth of a trillion pounds in today’s money. The estimated value of the gold mined in South Africa to the benefit of shareholders on the world’s stock exchanges between 1900 and 1950 is in the region of £1,493 trillion—43,000 tons at a conservative price of £938 per ounce. I’ve been unable to find an equivalent value for South African diamonds extracted in the same period.

The “earnest but fussy and faddy minority” Conan Doyle refers to were those parliamentary Liberals, including David Lloyd George, who opposed the war on principle, and the so-called Little Englanders such as Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Gladstone, previously, who had opposed British imperial expansion in general.

Lloyd George “…based his attack firstly on what were supposed to be war aims – remedying the grievances of the Uitlanders and in particular the claim that they were wrongly denied the right to vote, saying ‘I do not believe the war has any connection with the franchise. It is a question of 45% dividends’ and that England (which did not then have universal male suffrage) was more in need of franchise reform than the Boer republics. A second attack came on the cost of the war, which, he argued, prevented overdue social reform in England, such as old age pensions and workmen's cottages. As the fighting continued, his attacks moved to its conduct by the generals, who, he said (basing his words on reports by William Burdett-Coutts in The Times), were not providing for the sick or wounded soldiers and were starving Boer women and children in concentration camps.” (Wikipedia)

This was typical, in the opinion of Conan Doyle, of the “idealism” and “restless conscientiousness” that were “two of the most dangerous evils from which a modern progressive State has to suffer.”

With that petulance out of the way, we find him in a more sombre mood, the significance of the war weighing heavily on his fountain pen:

The first Boer War still smarted in our minds, and we knew the prowess of the indomitable burghers. But our people, if gloomy, were none the less resolute, for that national instinct which is beyond the wisdom of statesmen had borne it in upon them that this was no local quarrel, but one upon which the whole existence of the empire hung. The cohesion of that empire was to be tested. Men had emptied their glasses to it in time of peace. Was it a meaningless pouring of wine, or were they ready to pour their heart’s blood also in time of war? Had we really founded a series of disconnected nations, with no common sentiment or interest, or was the empire an organic whole, as ready to thrill with one emotion or to harden into one resolve as are the several States of the Union? This was the question at issue, and much of the future history of the world was at stake upon that answer.

We can take any number of things from this. We can see him looking across the Atlantic with a mixture of admiration and envy. We can excuse his jingoism as unexceptional: certainly no more egregious than the party line of Lord Salisbury’s Conservative government, or the excesses of Kipling. And in the context of Brexit Britain it’s impossible not to read the unexpected irony in “that national instinct which is beyond the wisdom of statesman”.

But it’s the idea that the outcome of the Boer War would determine “the future history of the world” that seems so astonishing today. We could dismiss it as empty rhetoric if he didn’t come back to it time and again.

Discussing the fraught events that preceded the eventual relief of Ladysmith, we read: “For the instant the fate not only of South Africa but even, as I believe, of the Empire hung upon the decision of the old soldier in Ladysmith (General White), who had to resist the proposals of his own general (General Buller) as sternly as the attacks of the enemy.”

Roberts, Kitchener and his other generals (apart from Buller) are emphatically courageous, calm in crisis, noble in defeat. His officers are unfailingly valiant. His infantrymen are brave, proud, and unflinchingly true to their fellows, their superiors, their regiments, their country, and their flag.

The Boers are bearded, cunning and doughty. The battles are thunderous and bloody. A strategic kopje overlooking Ladysmith is gained by a suicidal British assault. Conan Doyle reflects, “A hundred and seventy killed and wounded was a trivial price to pay for such a result.”

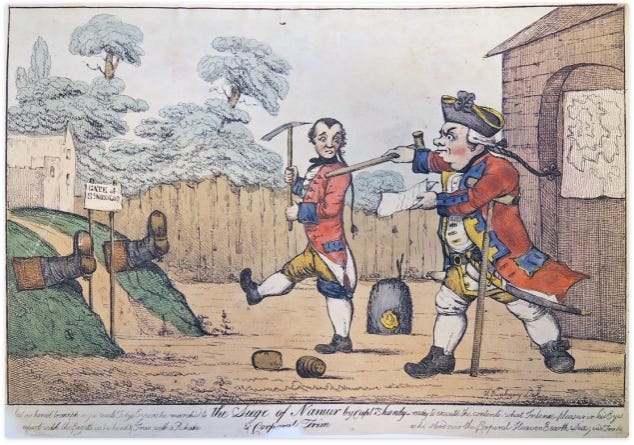

He fusses over the tactics of a less fortunate incursion like Uncle Toby fussing over his model fortifications in Tristram Shandy:

“Eleven officers and one hundred and fifty men were our losses in this unfortunate but not discreditable affair, which proves once more how much accuracy and how much secrecy is necessary for a successful night attack.”

He is clear about the rules of racial engagement: “From all the men of many hues who make up the British Empire, from Hindoo Rajahs, from West African Houssas, from Malay police, from Western Indians, there came offers of service. But this was to be white man’s war, and if the British could not work out their own salvation then it were well that empire should pass from such a race.”

My italics.

He mourns the loss of a promising young officer the way a rugby coach mourns the injury that will keep a promising young scrumhalf out of the next Test.

He attributes the mistakes of General Buller at Colenso to his “exaggerated respect for human life.”

Again.

Any minute now a figure will emerge before you from the fog of war, his bayonet fixed, his heart afire, and single-handedly Harry Flashman will storm the “kopje” to silence the guns of the enemy.

Perhaps the novelist in him couldn’t refrain from inflating the consequences of a British failure for dramatic effect, as if there might have been readers out there who would pick a copy of The Great Boer War in the expectation of being told a ripping yarn, the excitement of which would be diluted if they knew how it ended. But if we take the gravity of his concerns at face value we must assume that the future of the Empire and the world at large must have looked especially rosy to him and his readers when the last of the Boers surrendered in May 1902.

By securing “the keystone of the imperial arch” the continuity of Empire would have seemed to have been assured forever. When in 1909, ignoring the appeals of John X. Merriman and Sir Walter Stanford for a universal franchise, the British Parliament passed the South Africa Act, they would have seen the creation of the Union of South Africa as the consecration of eternal peace and prosperity for all the country’s citizens.

We are left to guess what a British defeat would have looked like in the Edwardian imagination, and to marvel at the difference between how much South Africa mattered to Britain then and how little South Africa mattered after 1910.

I might have found Wilson’s and Conan Doyle’s accounts less repulsive, and Deneys Reitz’s so dispassionate by comparison, if they hadn’t raided the landscapes of my early years, trampled on such sacred ground, and woken the ghosts of so many personal memories.

“It was upon October 30th that Sire George White had been thrust back into Ladysmith. On November 2nd telegraphic communication with the town was interrupted. On November 3rd the railway line was cut. On November 10th the Boers held Colenso and the line of the Tugela. On the 14th was the affair of the armoured train. On the 18th the enemy were near Estcourt. On the 21st they had reached the Mooi River. On the 23rd Hildyard attacked them at Willow Grange.”

Reading this passage of The Great Boer War in London in 2022 takes me back to late spring at New Dell in 1965. But it superimposes on the palimpsest of those memories the late autumn of England 1899 where the first copies of Heart of Darkness are being delivered to Blackwell’s of 50 Broad Street, Oxford.

Here in Natal the first rains of summer are overdue. I can hear the hooves of the British cavalry on the hill where Bruce buried that porcupine. I can see the tents of their encampment from New Dell’s front veranda. Something is moving in the Bunga-Bunga jungle. A twig breaks. A hadeda is startled into a flapping screech. That faint click is a cartridge slotting into the breach of a Mauser.

My father is driving Helen and me to Estcourt Junior School. Here is the railway bridge where Bruce and I met the man in the suit. In the streets of Mooi River women are balancing zinc baths on their heads, their babies strapped to their backs. The green hills tell us we’re still at home. Terrible things have happened on Griffin’s Hill. Willow Grange tells us we’re still alive. The thorn trees in the pale veld tell us that hell is around the corner.

We pass a galloping dispatch rider with tears in his eyes and blood on his spurs. The boom of a Creusot echoes over the Lowlands. We want my father to press on past Colenso and over the Tugela to Ladysmith, to Newcastle, to Vryheid—to anywhere but Estcourt.

And further back, to the rugged Eastern Cape and Lady Grey, the town of my birth. This is from Conan Doyle’s The Great Boer War: “Here and there in towns which were off the railway line, in Barkly East or Lady Grey, the farmers met together with rifle and bandolier, tied orange puggarees round their hats, and rode off to join the enemy. Possibly these ignorant and isolated men hardly recognised what it was they were doing. They have found out since.”

That’s my father with a rifle. That’s my mother he’s leaving behind. And the cruelty of Conan Doyle’s “They have found out since” stings like a sjambok.

This is Deneys Reitz’s view of the same landscape:

“Our course, later in the afternoon, took us up a mountain-pass, and when we reached the top towards evening, we could see in the distance the comfortable hamlet of Lady Grey nestling to the lest, while in a glen below was the old familiar sight of a British column, crawling down the valley. This gave us no anxiety, for being without wheeled transport of any kind, we turned across the heath and easily left the soldiers behind.”

It’s the same place at the same time, but the contrast in tone could hardly be more telling.

Reitz was educated at Grey College in Bloemfontein and wrote Commando in English, based on the notes he had made in the journal he carried with him throughout the war.

When it ended in May 1902, Deneys Reitz refused to sign the official surrender and was given ten days to leave the country of his birth. The last few paragraphs of Commando are pathetic in most trenchant sense of the word:

As we were waiting on the border at Komati Poort, before passing into Portuguese territory, my father wrote on a piece of paper a verse which he gave me. It ran:

SOUTH AFRICA

Whatever foreign shores my feet must tread,

My hopes for thee are not yet dead.

Though freedom’s sun may for awhile be set,

But not for ever, God does not forget.

…and he said that until liberty came to his country he would not return.

He is now in America and my brother and I are under the French Flag in Madagascar.

We have heard of my other two brothers. The eldest has reached Holland from his prison camp in India, and the other is still in Bermuda awaiting release.

Maritz and Robert de Kersauson are with us in Madagascar. We have been on an expedition far down into the Sakalave country, to see whether we could settle there.

General Gallieni provided us with riding-mules and a contingent of Senegalese soldiers, as those parts are still in a state of unrest. It was like going to war again, but all went quietly, and we saw much that was of interest—lakes and forests; swamps teeming with crocodiles, and great open plains grazed by herds of wild cattle. But for all its beauty the island repels one in some intangible manner, and in the end we shall not stay.

At present we are eking out a living convoying good by ox-transport between Mahatsara on the East Coast and Antananarivo, hard work in dank fever-stricken forests, and across mountains sodden with eternal rain; and in my spare time I have written this book.

Antananarivo, Madagascar, 1903.

This is the stuff that left me so speechless in that last podcast:

http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/unconventionalsoldiers/propaganda-the-authors-declaration/

https://core.ac.uk/download/30695558.pdf

Remind me to tell you about Wells, Hardy and C.F.G. Masterman. And why George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey and E.M. Forster weren’t invited to Wellington House.