Manners are the hypocrisy of a nation.

Honoré de Balzac

The problem with White English Anglican Sarf Efrikin Liberals like me is that we believe we were born good.

Yes, WEASELS were born to be the goodest, the nicest, the politest and the most well-meaning people from Agulhas to Beit Bridge, from Lady Grey to Ladysmith, and probably from Toronto to Perth as well.

We believe it in our heart of hearts. We believe it in the way the word believe derives from the Proto-Indo-European root word leyp, which means to stick like glue.

And the very simple reason we are stuck like glue to the conviction of it is because WEASELS like us have good manners.

At home in South Africa, the manners of the WEASEL appear to distinguish it as morally superior to the blunt Afrikaner, the rude Portuguese grocer, the sweary Greek Cypriot baker, the flashy Joburg kugels and bagels, the foul-mouthed Cape Coloured, the fire-breathing Zulu, the cringing Mosotho, the double-dealing Indian and all the other non-WEASEL South Africans we were brought up to stereotype as racistly as I just have. In the nicest and kindest possible way, of course.

But transplant a WEASEL to England, the heart and home of truly good manners, and the WEASEL very soon discovers that its manners, which seemed so uniquely admirable in South Africa, are regarded by the actual English, in their politely quizzical English way, as just as clumsy, boorish, insolent and disagreeable as the WEASEL formerly regarded the clumsy, boorish, insolent and disagreeable lack of manners of its white Afrikaans counterpart back home.

The English won’t say, “Siestog” or “Shame, man” when they observe a lapse in our social etiquette. They will say, “Oh dear.”

Failing that bracing corrective, the WEASEL will continue to think of itself as having been infallibly blessed to be bottomlessly benign from birth.

Herein lies the problem:

We believe we have good manners because we believe we were born good. We imagine that the little foetuses of ourselves were conceived in goodness; that some endogenously holy Anglican spirit of goodness was mainlined umbilically into our intrinsically sweet little burgeoning bloodstreams in a lily-white meiosis of Mary-like immaculacy and Jesus-like innocence, and that we arrived in the world with a stork-like purity ontologically vaccinated against the remotest possibility of growing up to display anything but the most impeccable of the most ladylike or most gentlemanly of Anglican good manners.

It’s the other way round, of course. Our good manners make us think we are good. We are stuck with glue to our conviction that we were born good because we had all our un-Anglican bad manners trained, educated, coaxed, bribed or beaten out of us.

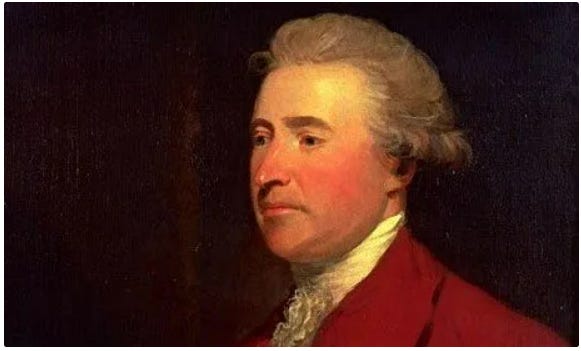

Just like our parents had. And just like their parents had. And so on, all the way back to one Edmund Burke.

Don’t beat yourself up if you don’t know very much about Edmund. I didn’t either until I began to wonder where I got these nice, polite, impeccably well-mannered English traits from.

You may remember that my journey in search of the lost and legendary electro-plated-nickel-silver goblet containing the essence of Englishness began in 1833 when I joined Ralph Waldo Emerson on his first trip to England. He was going to the motherland to find out where his English traits came from, and how they got into his system. If he could find a way of identifying them and rooting them all out, the question would then be whether there was enough left in his social, psychological and spiritual make-up to constitute anything like an authentic American self.

There was.

I had the same question — the itch I could never scratch: What would my South African self look and feel like if I could thoroughly dry-clean my brain of all the grey English fluff that had flown into my head by mistake, courtesy of the bards, the novelists and the fabulists exactly like A.A. Milne? Would there be anything left to write home about? And where would home be if there was?

Emerson wrote his English Traits in 1856. This is me trying to figure them out in 2023.

Some rabbit holes don’t have any rabbits in them. I got lucky in my search for the furry fountainhead of my English manners. Eventually. In a rabbit hole so deep it took five years to get to the bottom of, I found the culprits responsible for making me as ignorant as the etymology of niceness tells me I am.

The deeper I dug, the less I digged them. I had to break through the crusty layers of crap left behind by Harry Potter, C.S. Lewis, Tolkien and the Allahakbarries; to burrow below the sopping sewers of Victorian sanctimony and the stubborn sediments of the sentiments deposited in the 19th century by the successive imitators of Austen, Fielding, Swift and Defoe. And there in the late 18th, at the very, very bottom of all the many, many cunicular culprits I had recognised along the way, was the most culpable cunicular culprit of them all — Edmund himself, the Burke of all berks.

What to say about Edmund Burke that won’t bore you to oblivion? Perhaps only this:

When the French Revolution happened, he shat himself. And he shat himself so profusely and so liberally and so relentlessly in such a shit-storm of rodomontade in and across and all over so many pamphlets, periodicals, speeches, books, letters and public opinions about so many subjects aesthetic, moral, political, philosophical, parochial, international and religious it was inevitable, sooner or later, for his admirers to find enough tiny fragments of shit-covered shards of undigested Burkean jewels in England’s shit-flooded rivers and on its shit-covered beaches to crown him in retrospect as the Father of Modern British Conservatism.

Hats off to the Modern Tories for following his example so literally.

I’ve raised his shit-stained spectre from the reservoirs of Thames Water to make one simple point: Burke prized manners above morals. He prized manners above principles; he prized them above and beyond any notions of justice, fairness, equality, truth or freedom. He prized manners especially — and very deliberately and angrily — above any consideration of the idea of universal human rights.

A lot of people talk a lot of shit about what they stand for. Even in the mouths of monsters it can sound logical, sensible and agreeable. It’s only when you discover what someone is against that you get to know their true motivations. And the locus of it will always be found in the specific fears or types of disgust their words are designed to rationalize away.

Nationalism is disgust for outsiders expressed as pride in one’s country. Conservatism is a fear of change expressed as not rocking this comfy little million dollar yacht of mine. Put them together and you get The Edmund Burke Foundation, “...founded in January 2019 with the aim of strengthening the principles of national conservatism in Western and other democratic countries.”

If that doesn’t send shivers down your spine, turn away now.

The existence of this radioactively-toxic club of quite possibly the most entitled, fearful and disgusted people on the planet was brought to my attention by the relentlessly brilliant David Aaronvitch. If you’re not reading his Notes from the Underground on Substack you’re not keeping up with just how cynically the cynics are taking us fools for fools.

Burke’s nemesis — the man who inspired the most spine-shivering fear, disgust and loathing in him — was Thomas Paine, the revolutionary firebrand, the great English individualist, the spiritual godfather of the American Constitution, and the author of The Rights of Man, the book that made Edmund shit himself for the last six years of his well-mannered life.

I’ll skip the painful history of how their enmity ended up dividing the western world into pr*cks and c*nts, more politely known as Left and Right, to treat you instead to the pithiest and most revealing of their differences of opinion.

Here’s what Burke said about trying to change the world for the better:

A spirit of innovation is generally the result of a selfish temper and confined views.

Edmund Burke

And here’s what Paine said about changing the world for the better:

Moderation in temper is always a virtue; but moderation in principle is always a vice.

Thomas Paine

This what Burke said about religion:

The principle of religion is that God attends to our actions to reward and punish them.

Edmund Burke

And here’s what Paine said about it:

The whole religious complexion of the modern world is due to the absence from Jerusalem of a lunatic asylum.

Thomas Paine

Burke was the Patron Saint of Gradualism, the Inventor of the Long Grass into which the thorniest issues of the political day are tossed until everyone forgets they were an issue. His was the voice in Thatcher’s head telling her that South Africa’s ‘non-white’ peoples should get the vote only when they were ready for it. He was the St Paul of obfuscation, revisionism and cant. He insisted on manners because he had no morals. He put vanity before values, piousness before principle, and form triumphed over substance. Paine stood against everything he was, and stood for everything he wasn’t.

So, yes, fellow WEASELS, we got our good manners from Edmund. And whether we know it or not, we got our good hearts from Thomas.

Not all good manners are hypocritical. I like people who smile and say please and thank you. I don’t like it when the crowd in the Arthur Ashe stadium clap and cheer a double-fault. Unless it’s against a player with bad manners.

But Balzac was right. Good manners are a poor substitute for the honest truth.

I’ll leave the last words to two of America’s greatest philosopher-poets:

To the real artist in humanity, what are called bad manners are often the most picturesque and significant of all.

Walt Whitman

Values are like fingerprints. Nobody is the same, but you leave them all over everything you do.

Elvis Presley

**Just good WEASEL manners.