There is not one but many silences, and they are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses.

Michel Foucault - A History of Sexuality, Volume 1, An Introduction

There is no evidence to prove empirically that the white, Anglican, English-speaking community that constituted less than seven percent of the population of the South African province of Natal in the 1960s was the most sexually repressed society in the world. These things are hard to measure.

Sexual repression doesn’t show up in the usual demographic or usage-and-attitude studies because, unlike dairy products, cancer or microchips, there isn’t a lot of money to be made from it.

Unless you’re Durex or Pornhub.

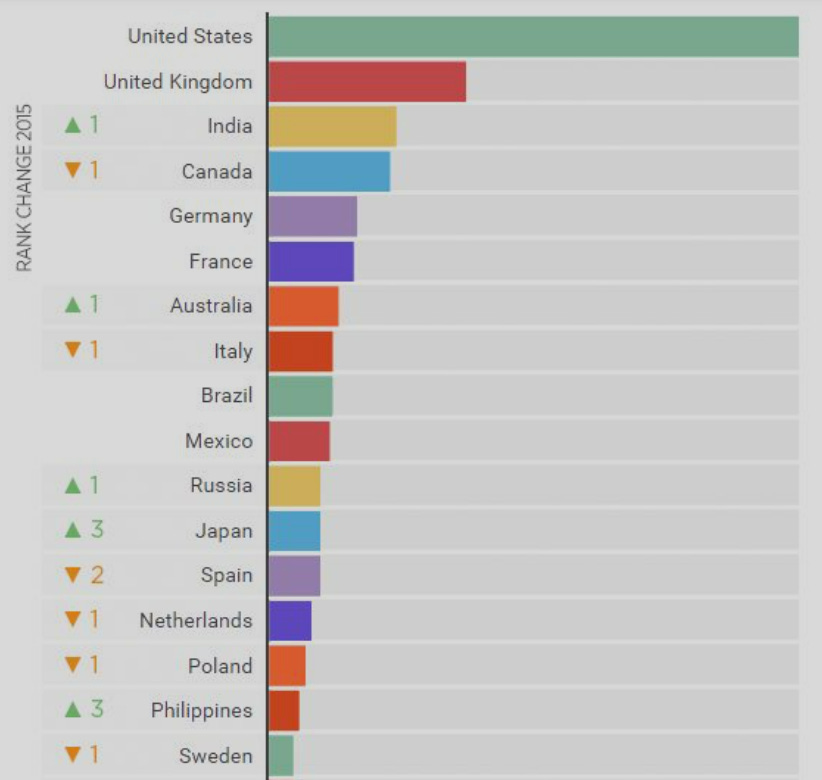

In a recent study by the condom maker that ranked the nations of the world by their self-reported degree of sexual fulfilment, Japan came a limp last. When you dig into the data explaining the disappointing performance of the people of the land-of-the-apparently-not-so-rising-sun, it turns out, astonishingly: “...an important major reason is that they are not having sex.”

https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/nation/the-world-s-most-sexually-satisfied-countries-durex-survey

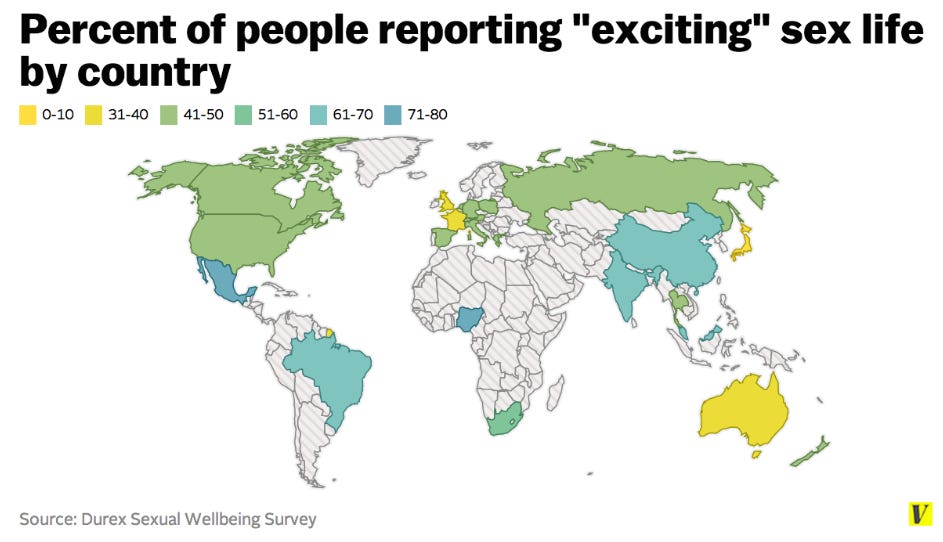

Mexico & Nigeria - wtf?

But note the UK, Australia and Japan.

You’d think that people who watch a lot of porn would be the least sexually repressed. But intuition, my desperately limited experience in this arena and these two charts, above and below, suggest the opposite: that the people who report having the most “exciting” sex lives are the ones who are watching the least porn. Or, vice versa, that the people who are watching the most porn are having the least exciting sex lives. There seems to be a sweet spot somewhere in the middle where a fair amount of both makes the world go round.

But correlation, of course, is not causality, so make of this what you will. I have.

Porn traffic by country:

Three wildly unsubstantiated presumptions appear to me to emerge from it:

Englishness is not sexy. The closer you get to the Englishness of England, the less sexy and the more prurient you become. And the closer the codes and conduct of the milieu you grew up in were to approximating the codes and conduct of the milieu of Victorian England, the more prudish, proper and repressed you’re likely to be. But we knew that sex was never supposed to be fun:

Lie back and think of England.

Queen Victoria’s advice to brides-to-be in the late 19th century, possibly apocryphal. Popularized by the 1955 translation of Pierre Daninos's 1954 Les Carnets du Major Thompson, a French satire on upper class British culture.

The Natal Midlands in the 1960s were precisely that place, a patch of England’s green and pleasant land trapped in a late 19th century conception of English mores and morals. Our ignorance was embarrassing. And the more embarrassed we became by our ignorance, the more ignorant we became.

Take this and locate it now in the wider milieu of the Afrikaner Calvinist’s draconian censorship of every hint of a possible suggestion that babies didn’t arrive directly from heaven pre-swaddled in blue or pink blankets redolently sprinkled with Johnson’s (allegedly cancerous) baby powder and you’ll understand why I was so shocked, at the age of sixteen years and nine months, to see my first, yes, actual female nipple.

Like a red hot branding iron sizzling into the pure white rump of a Friesian dairy cow, the accidental slip of the right cup of Maureen van der Westhuizen’s bikini top at the Estcourt Municipal Swimming Pool was enough to sear it in my virgin imagination forever. It took less than an instant for her to cover her shame; a little longer to recover her dignity.

But my glimpse of it would become the treasure, the charm, the symbol, the phylactery — the single talismanic Memento Vivere that inspired me to survive 1971’s twelve months of damnation that, in a universe only slightly different from this one, would otherwise have seen an hysterically bosbefokked version of my nice English self switching his RI rifle to automatic and emptying its magazine of twenty 7.62×51mm bullets into the officers’ mess of the motorized infantry unit of the Fourth South African Infantry Battalion that overlooked Kipling’s grey, green, greasy Limpopo.

They can thank Maureen that I had something to live for.

It was this excruciatingly embarrassing reflection that inspired me to ask Google if there was any place on earth more sexually repressed in the 1950s and 1960s than the white, English-speaking Natal Midlands.

There was. We were beaten by Ireland’s Inis Beag. But only by a ball-hair.

Inis Beag circa 1966 was a rural community of 350 people, primarily of fishing/farming lifestyle. Their beliefs around sex? That it's dangerous and unhealthy. Many people wish to not participate in sex at all, but marriage, arranged by parents, deemed it a duty. So dutiful sex happened between married adults and in some relationships strictly for procreation. This was in the man on top position, during which partners wore smocks to cover as much of their bodies as possible while trying to finish as soon as possible.

Foreplay was limited to light kissing and groping of the buttocks, no heavy petting, no oral sex. They probably did have anal sex, but unintentionally as a result of anatomical ignorance. Masturbation was taboo, exploration of bodies, their own or others' taboo: sex talk: taboo, if people were sexually expressive in public, they were severely punished, dogs licking their genitals were beaten. People in Inis Beag grew up without language, permission, or education to understand their natural experiences of sexuality, and as a result, experiences like menstruation, childbirth, menopause, were terrifying.

Ref: https://nerdfighteria.info/v/6CqJNo12rPs/

I don’t know what my parents did in bed. No one wants to think about the circumstances of their conception. Ever. But our dogs weren’t beaten for licking their things. It took just one sharp word from my father to have them scurrying out of the house with their tails between their legs.

Shame.

So I’m no longer too embarrassed to admit that the most compelling reason why so many of us in the Estcourt High School English “A” Class of ‘68 converted so wholeheartedly to communism, most notably and most avidly those of us who had spent our adolescent years living in same-sex boarding hostels, had less to do with the theoretical economic, social or even moral benefits that would derive from workers owning the means of production, and a lot more to do with the very practical and significantly more tangible benefit of exponentially improving our chances of one day having sex with the opposite sex, if not with the opposite colour.

We had heard about communes in theory. We understood that some white communists lived in communes. And that some white men and women who weren’t even married lived in communes. Together. It was even more thrilling to learn that you didn’t have to be either a communist or a man to live in one. You just had to be white.

And if you weren’t a communist to begin with, living in a commune made you a communist by definition whether you believed that workers should own the means of production or not. And hence, to cut to the chase, it might lubricate your entry into a commune if you were a communist already.

And, furthermore, that even if apartheid lasted another thousand years, which seemed like a very realistic prospect in 1969, there was nothing in the Immorality Act that prevented white men and women having sex, like, with each other. Or was there?

We read it again to make sure:

The Immorality Act, 1957 (Act No. 23 of 1957; subsequently renamed the Sexual Offences Act, 1957) repealed the 1927 and 1950 acts and replaced them with a clause prohibiting sexual intercourse or "immoral or indecent acts" between white people and anyone not white. It increased the penalty to up to seven years' imprisonment for both partners.

Wikipedia

Phew.

It was a little more complicated it you were gay. Between 1948 and 1994, “homosexual acts” were also punishable by up to seven years in prison.

On the other hand, the punishment for being a communist was significantly more severe:

The Suppression of Communism Act, which came into effect on 17 July 1950, defined communism as any scheme aimed at achieving change—whether economic, social, political, or industrial—"by the promotion of disturbance or disorder" or any act encouraging "feelings of hostility between the European and the non-European races [...] calculated to further [disorder]". The Minister of Justice could deem any person to be a communist if he found that person's aims to be aligned with these aims, and could issue an order severely restricting the freedoms of anyone deemed to be a communist. After a nominal two-week appeal period, the person's status as a communist became an unreviewable matter of fact, and subjected the person to being barred from public participation, restricted in movement, or imprisoned.

Wikipedia

So in just the same way (in those days) that any growing boy who preferred girls to rugby was automatically classified as a “homo”, you were fucked if you did and you were fucked if you didn’t.

This would be a lot more amusing if the irreparably tragic consequences of these few examples of apartheid’s legislative instruments on the lives of hundreds of thousands of individual people hadn’t been actively enabled, if not publicly endorsed, by the apartheid government’s great anti-communist friends in the UK, the USA, Israel, Taiwan and those other shining exemplars of democracy in Spain, Portugal, Chile, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and too many elsewheres to remember.

History isn’t a very good judge of history. If it were there would be no doubt that the crimes committed in the name of anti-communism in Africa, Europe and Latin America were more horridly brutal, numerous and heinous than all the crimes committed on behalf of it.

But, hey-ho, let’s go where the fun is, as Rocco says.

Because four years later I put my communist theory in practice.

It happened one night in March of 1972 when I could no longer stand the sound or the smell of the testosterone toxicity of the all-white, all-male residence of William O’Brien, aka Willy-O-B, on the southern perimeter of the all-white campus of the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg. I had had ten years of all-male, all-white company in boarding schools. I had survived another year of it in the SADF. I had had enough.

In fewer seconds than it takes to have a second thought, I had packed my green SADF-issue kitbag with all my three t-shirts, skants and Silas Marner, and fled for freedom.

Freedom was a flat in Boom Street where Maclagan lived with a gay poet and a chemistry dropout. Maclagan and I would have a long, rich and highly educational relationship. The gay poet would become a life-long friend. The chemistry dropout had dropped out of chemistry not long after mastering the skill of turning ergotamine tartrate into lysergic acid. My subsequent meetings with him would be by appointment only.

It was my first commune.

In the USA they call it cohabiting or cohousing. Or they call them house-shares. In the UK they call them digs for the diggers who dug the diggings. Brazilians nod to the liberating political spirit of communal living arrangements freed from the autocratic monarchs of unelected mothers and fathers by calling them republicas.

How they came to be called communes (origin French, ME & OFr < ML communia, orig. pl. of L commune, lit., that which is common) in South Africa, one of the most un-French and anti-communist countries in the world, remains a mystery.

The only French we knew was Inky Pinky Parlez Vous. The first time I heard French actually spoken, by the elderly woman who sat next to me on my first plane journey to Europe in 1972, I wanted to shout out for medical assistance to help her control the Tourette’s-like stream of unintelligible blather issuing from her mouth. Then I remembered not to make a fuss.

It’s odd that we grew up despising the French without knowing anything about them apart from what we had gleaned from our Lion and Tiger comics and from the fantasies and the fairytales of the Edwardians that were the staples of our earliest literary memories. And the vague idea that they were somehow sexy.

Oh.

In Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves notes:

Anti-French feeling among most ex-soldiers amounted almost to an obsession. Edmund, shaking with nerves, used to say at this time: "No more wars for me at any price! Except against the French. If ever there is a war against them, I'll go like a shot." Pro-German feeling had been increasing. With the war over and the German armies beaten, we could give the German soldier credit for being the most efficient fighting man in Europe ... Some undergraduates even insisted that we had been fighting on the wrong side: our natural enemies were the French.

So, no, I never thought to examine the origins of “commune” at the time. The liberating spirit of living in a small, non-hierarchical community of fellow human beings had nothing to do with politics, and everything to do with discovering Captain Beefheart, the limits of the Kama Sutra, DP*, and just how long it takes to boil a mealie. Simultaneously.

Skipping rapidly forward from the particular to the general, commune living by (mostly) young, white, middle-class, (usually) English-speaking South Africans in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s is a sorely neglected subject of research into the sociology of the most fraught, fractured and final decades of apartheid.

By the early seventies they had sprung up in all the major cities: in Joburg, Cape Town, Pretoria, Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Bloemfontein, Port Elizabeth and East London. We heard there was even one in Boksburg.

Like criminals, the most famous communes were the most notorious ones. And the most notorious ones, as measured by the availability and diversity of their communal supply of music, alcohol, drugs and (shamefully) nymphomaniacs, were naturally the most attractive. Nymphomaniac was the hypocritically derogatory and misogynistic word men used at the time to describe a woman who liked sex for the sake of it. Which is to say someone like a man.

Less well-known and less understood, because their role in it was necessarily a carefully guarded secret, was the part many of these communes played in sheltering both black and white political dissidents who were on the run from the Bureau of State Security (BOSS), apartheid’s version of Stalin’s KGB, and — especially after the Soweto riots of 1976 — serving as safe houses for suspected “terrorists” seeking passages north to the very relative political immunity still being provided by the governments of Botswana and Mozambique.

Most of us didn’t sign up for the politics. We signed up because we needed affordable places to live. And if an affordable lodging happened to come with one or more of the legendary fringe benefits that had reached us through the pre-WhatsApp grapevine of meeting actual people and talking to them, well, happy days.

The sex was noisy, crude and optional. The politics were discreet, sophisticated and inevitable. I still don’t know how it worked, the latter.

Somehow or other, by chance, the opportunism of desperation, or through the astute design of people in the anti-apartheid underground unknown to BOSS, the communes I lived in in Joburg and Cape Town, and the ones I knew about in Durban, PE and Bloemfontein, all agreed to “take someone in” when the need arose.

The procedure was simple. The only phone in the house would ring. You would answer with the name of the commune.** A voice, usually in white or black English, would say, “Do you have a room?”

You would answer, “How long?”

The reply would be specific — one night, two nights, four nights. Usually no more than a week.

You would answer yes or no. If you answered yes you would be given a day of the week, but never a time, a name, a colour or a sex.

If you answered no, they would say thank you, and put down the phone before another breath could be drawn.

You knew it would be between midnight and dawn. You announced to the house that they would be having a “visitor”. You prepared a bed and a plate for food.

An hour before midnight, one or two of you would take a casual stroll up and down the street outside your house. You would be looking for unmarked police cars. Typically it would be a man in the driver’s seat drinking a half-jack of brandy and pretending to read a newspaper. If you saw one you would give him a friendly smile, stroll back to the house, and switch on the veranda light. The unknown driver of the car bringing the visitor would know not to stop.

The visitors could be male or female. But all of them would be young and terrified. They would leave their assigned bedroom only to visit the bathroom. Food would be delivered to their door.

You would know not to study the features of their faces in case the worst happened. The less you knew, the safer you would be. It goes without saying that black people were not allowed to live with white people by law. Harboring a black political activist multiplied the jeopardy by a thousand.

The “communists” in the communes who arranged, aided or abetted these visits weren’t political activists. They were ordinary white people with ordinary jobs. They were young medical students, trainee electricians, legal secretaries or junior sub-editors working for the SABC, like me.

I started a commune of my own and I still didn’t find out who was behind it, how it operated, who got my phone number, or who was on the other side of the phone. It just happened. I can only think it was because good people are inclined to do good things. Them, not me.

Or perhaps it was the least we could do.

In Foucault’s terms, the two significant silences that permeated South African discourse were, and always had been, associated with sex and politics. Both were taboo subjects. Race or sex, both aroused the same feeling of unspeakable longings for a more gratifying, satisfying, more rewarding coming together. Sex was the flip-side of apartheid. Apartheid was the opposite of sex: the unnatural fracture of a natural union. The words used to think them were simultaneously political and sexual: apart or together. Silence spoke for both of them.

Apartheid was a crusade against closeness, a sustained assault on the possibilities of affinity and affection, a monstrous rage against the merest suggestion of mingling, a holy war against intimacy, a criminalization of communalism. It was a demonization of differences — racial, cultural, linguistic and sexual.

It was inspired by the fear of feeling and the terror of touch.

It’s in the name — apartness.

And in all of these observances it was a consummately British creation.

It was Cecil John Rhodes, that great hero of British Imperialism, who laid the legal foundations for racial discrimination in South Africa. It was the Boer War that tested their British faith in it, sharpened their appetite for more of it, and funded their realization of it abroad and at home.

It was Arthur Conan Doyle and his fellow Edwardians who so successfully dramatized the fear of infection that other races and cultures might bring to taint the pure white body politic of Great Britain that even today, when actual shit is flowing through the rivers and onto the beaches of England, it’s the dog-whistle politics of the “small boats” that can still hypnotize the impoverished masses of the Great British Public to sustain the apartheid of English class that successive generations of wealth and entitlement have made in the image of Rhodes, Malan, Verwoerd, Vorster and Botha.

It was George Orwell who saw it: “Before the war, and especially before the Boer War, it was summer all year round.”

Big boats wouldn’t do it. It their smallness that makes them into germs.

Somehow, somewhere I got infected. But I’m getting better now.

Onwards to Cyril, the consummation, the brinjal, Jeremy Taylor and Middlemarch.

*Durban Poison is known the world over as the crudest and most effective marijuana-hit money can buy. Its culinary equivalent would be a s’more.

**Communes were usually named for the streets they were in. The one I started in Joburg was Quince Street. Ah, mems. I met Cyril in Tolip Street. Ah, more mems. My brother Andy had a notorious commune in Durban called What’s Your Favourite Colour. Which is how they answered the phone.