Anger's my meat: I sup upon myself,

And so shall starve with feeding.

William Shakespeare’s Coriolanus

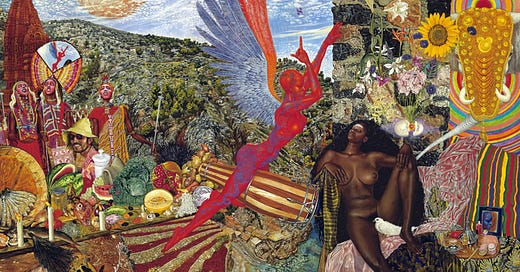

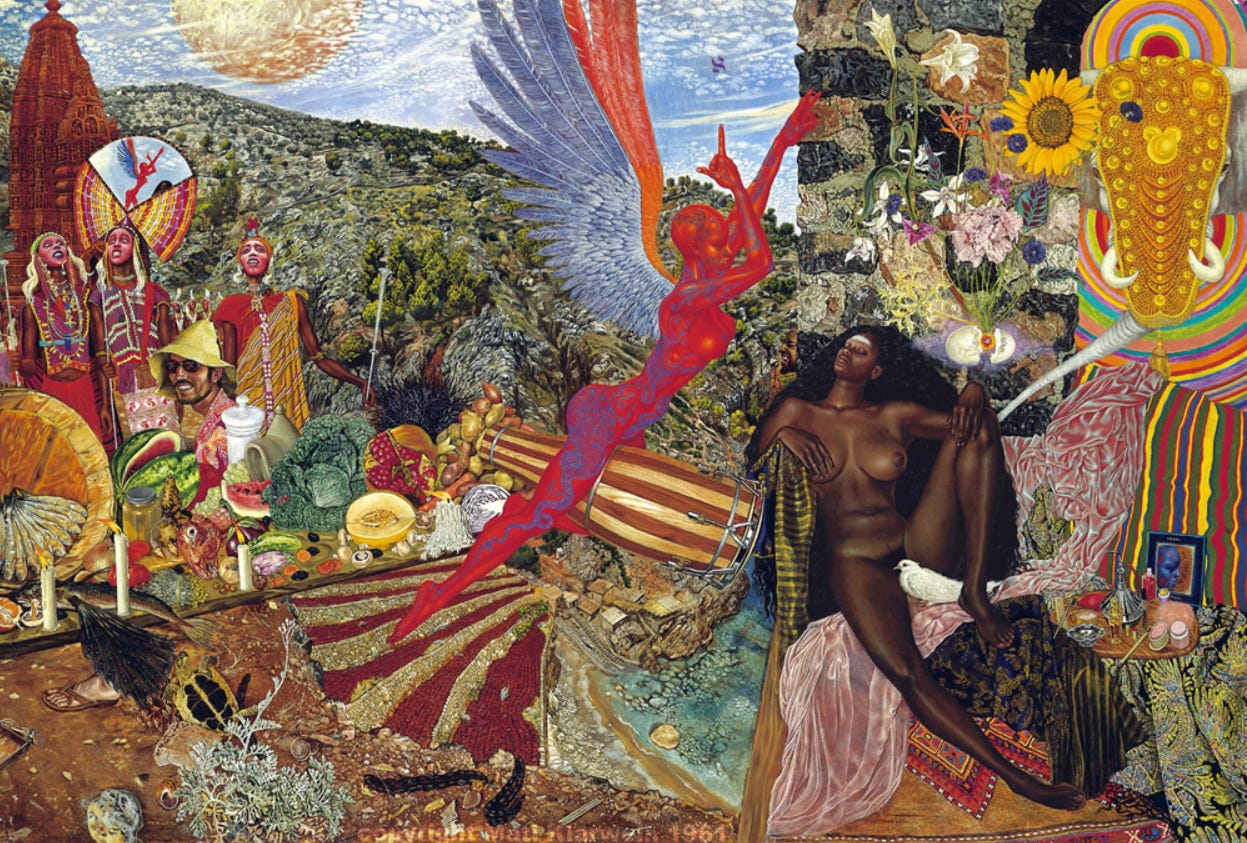

It’s wincingly trite and flinchingly predictable but I’m going to say it anyway because it’s true: the soundtrack of my sex education was Carlos Santana’s Abraxas.

An Ἀβρασάξ was an amulet of random Greek letters originally supposed to have magic powers. In the 2nd century it was personified by the Gnostics as a deity that radiated divine emanations, or good vibes as we would soon be calling them.

The unmitigated sixties hippyness of my initiation is mitigated more than somewhat by placing it in Boom Street, Pietermaritzburg, and admitting that we were also listening to Chris Andrews, Jody Wayne, Neil Diamond and Mungo Jerry.

Maritzburg was a very long way from Woodstock.

I mention this not out of shame, pride or sentiment, but only to locate and contextualize South African commune life in the 1970s and early 1980s firmly in the sexual, social, cultural and political ethos of the 1960s. And hence to colour in some of the background against which it is possible to see, with some degree of nuance, how it wasn’t all that extraordinary for me to find myself sharing a house and a girlfriend with Cyril Ramaphosa.

Actually, on second thoughts, with more than a touch of sentiment.

Maclagan was Colette reincarnated. Why France’s most notoriously beloved woman of letters, the intellectual firebrand, the polyamorous creator of Gigi and the author of the Claudine novels, would have chosen to be reborn in Estcourt, Natal, in 1953 must remain forever a mystery. But remove only her pro-Vichy sympathies and Maclagan she was, but now in kaftans and sandals in a purple bedroom in Boom Street where the fumes of ambergris and dagga combined to exorcise such ghosts of sexual, political and societal conformity that had survived the transition from Masonic Estcourt to liberal Pietermaritzburg, the capital of colonial cool in our part of the world.

Durban had The Flames but we had the flowers.

Her father was a rough, gruff and fearsome Mason who worked at the Masonite factory in Estcourt, perhaps coincidentally. Every Friday night at six o’clock he would put on his hat with the guinea-fowl feather tucked into its brown silk hat-band and say, “Those goats won’t sacrifice themselves, you know.”

At three o’clock on Saturday mornings she would hear his Vauxhall Viva pulling up in the driveway, followed shortly thereafter by the sound of furniture being rearranged.

Her mother was a sweet and compliant bundle of nerves. Her older sister would be placed under house arrest in the seventies for being an alleged communist sympathizer. That might have had something to do with it.

Long before the women’s liberation movement crossed the Atlantic to reach the last outpost of Empire, Maclagan had figured out and embodied all of its ideas and aspirations in her manners, her dress and her language. She didn’t need Time to tell her God was dead, or Hair to tell her that her body was her own to do with as she pleased. She didn’t need The Beatles to teach her anything about love or loving, or the Stones to teach her anything about the ways and means of obtaining satisfaction.

When I was still quoting A.A. Milne, she was quoting Nietzsche. By 1969 she had dismissed the entire English canon in favour of the said Colette, Jacqueline Susann, Dostoevsky, Herman Hesse, Gore Vidal and the early translations of Julio Cortázar smuggled into the country by the Parisian friend of her sister.

Her scorn for Christianity was shaped by Hitler’s devotion to it. Her hatred of apartheid was fueled by the West’s blithe tolerance of it. Her political views were inspired by Marx and tempered by Orwell. She advocated the decriminalization of dagga on the grounds that you had to be permanently stoned to understand why Jesus-loving capitalists motivated only by greed, pride and uncontrollable lusts for self-aggrandizement, prestige and power held the moral high-ground over godless socialists who wanted to, like, share things with other people.

I will add only that she was a dedicated, tireless and imaginative teacher. May the nameless spirits of your genius bless you wherever you are, Beth Maclagan.

Thanks to our far-flung geography, our self-inflicted absence of television, our self-inflicted status as the most despised nation on earth, our severely limited access to information in general, our totally restricted access to all the information we were actually interested in, and in no small part to the apathy of our ignorance, the sixties arrived in South Africa some ten years after the rest of the world had discovered peace, love, hallucinogens, grooviness and The Pill. The felicitous consequence of this, for South Africans of my generation, was that our sixties lasted until 1981.

There’s some debate about when they officially ended in the rest of the world. Only the most mean-spirited of pedants would claim it was on the last day of the December of 1969.

I don’t want to get into a futile debate about this but I can’t help thinking the nail in the coffin of the sixties, in the actual world north of the Limpopo, wasn’t hammered in by British or American punks, revivalist mods, greasers, football casuals or Teddy Boys, nor even by John and Yoko leaving the UK for New York in 1971, but finally and definitively by the astonishing rise to fame of Rock the Boat by The Hues Corporation in early 1974, widely regarded as disco’s first global hit.

Up to now we sailed through every storm

And I've always had your tender lips to keep me warm

Oh, I need to have the strength that flows from you

Don't let me drift away my dear, when love can see me through

Our love is like a ship on the ocean

Thankfully you don’t need to read any more of its verses to get my point. The sixties died when people stopped listening to songs and started listening to music.

And luckily for my generation of white South Africans, we still haven’t heard it or heard of it. I found it on Quora, that raging bonfire of paranoia, delusion and occasional common sense where anyone who knows about anything or thinks they know about anything can throw it into the flames. With any luck the dross will burn to leave only the nuggets. It’s cool if only for the possibility of that.

For South Africans with beating hearts, the sixties officially ended on 20 January 1981 when Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the 40th President of the United States, replacing Jimmy Carter. We knew right then that all our hopes and dreams for peace, love and flower-power in a post-apartheid South Africa would have to be shelved for another decade or more. We were hopelessly right. With friends like Reagan, Thatcher and their best friends in some of the world’s worst countries, we really didn’t need any enemies.

Thinking about it now, it doesn’t seem like much of a coincidence that 1981 was also the year I got my first job in advertising. My fellow communists were shocked to the core. I had to remind them that my previous job was writing propaganda for the apartheid state.

Oh.

I spent the best part of 1978 in Cape Town living in a commune somewhere on the edge of the Cape flats where there wasn’t enough Port Jackson Willow to stop the wind-blown sand from gritting the butter, the bonhomie and the beds. I left some stories there, but came away with a righteous intolerance of righteous intolerance.

The commune was cool until the third time I went to buy vegetables at the Cape Town market in Epping for the other communes in our communal community of communes. There must be a collective noun for them that’s a bit more elegant than that. Maybe a collective. Or something in Chinese perhaps, like 中國?

There were six communes in our commune of communes, all of them within hi-jacking distance of Elsies River. The idea was simple. Every six weeks it would be your turn to buy and distribute vegetables for all six communes. Which meant waking up at three in the morning to get to Epping before all the independent grocers in the Cape Town area had picked off the best and the juiciest of last night’s harvest. But the post-hangover pain was well worth it, both financially and politically.

It wasn’t only significantly cheaper than buying retail, it also ticked a lot of our communist boxes: The farmers made more money by selling (almost) directly to the consumer, i.e. us. We avoided paying the extortionate market-capitalist grocer’s obscene profit margins. It gave us a better range and variety to choose from. And pooling the monetary contributions from all six communes gave us more bargaining power since we were buying in bulk.

And for the five weeks until your turn came round again there was something cheerfully, communally and lazily wonderful about waking up late on Saturday morning to find three large sacks stuffed with the juiciest and freshest fruit and veggies on your front porch. Juicy and fresh, yes, but strictly the proletarian basics, of course: apples, naartjies and bananas; carrots, cauliflower, pumpkins, cabbages and potatoes. And more proletarian potatoes.

It all went swimmingly until that wet and wintry July of 1978 when, in a sudden fit of unforgivably bourgeois madness, I decided that I would warm the cockles of the hearts of my collective brothers and sisters by setting aside some of the potato-designated money and treat them instead to three brinjals per household. My intentions were good, but the road to capitalism is apparently paved with them.

I discovered this when I was invited to appear before the Lansdowne branch of the three-person tribunal of tribunals of the collective of collectives and asked to explain myself. I explained what I just explained, but with no disrespect to the worthiness of proletarian potatoes. They sat me on a hard wooden stool in a windowless room somewhere in Wynberg while they paged through The Communist Manifesto, Das Kapital and The Little Red Book.

They consulted and whispered and consulted again. Eventually the blonde woman in the middle who was suckling a little black neonate announced to me and the empty room that while it could find nothing inherently counter-revolutionary in the brinjal per se, the committee was deeply concerned that a developing taste for the exotic vegetable could lead to a craving for figs, cream cheese and puff pastry.

She paused to allow the silence to stun me with the full weight of the implication.

“Yes,” said the partially bearded man in the Grateful Dead t-shirt. “Canapes.”

Which provided the perfect segue for the man in the hood and the lilac John Lennon sunglasses to sentence the last fond remnant of my reactionary soul to eternal shame:

A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.

Mao Tse Tung

Communism is cool until it isn’t.

I left Cape Town in search of expiation. I thought I would find it at Wits (The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg), specifically in the form of an Honours Degree in English Literature. I told myself I was going back to the well to drink deeply of those last dregs of the English inheritance I was still so clearly struggling to swallow.

By 1978 the political mood in Joburg, and across the Reef from Roodepoort in the east to Krugersdorp in the west, had taken a dark and violent turn. The monstrous John Vorster had been replaced as Prime Minister by the impossibly more monstrous P.W. Botha who, with the unqualified support of his anti-communist friends in London and Washington, was intent on proselytising the sacred Western values of apartheid throughout the godless regions of Angola, Mozambique and north of the Zambezi, by bloody force if necessary.

At home, the simmering discontent in the townships was spilling over into a disorganized and underfunded war against the increasing brutality of the South African Police. In February a bomb capable of destroying a 22-storey building was found in a Johannesburg office block and defused.

The South African Defence Force, the alma mater of my Greefswald, was increasingly being called upon to support the police in quelling the possibility of outright insurrections throughout the Transvaal townships, a literal stone’s throw away from where, in my little garden flat in Parktown, I was trying to figure out if Coriolanus was more like P.W. Botha than, say, Churchill or Mussolini.

It was then and there that an official brown envelope, forwarded from the address of my commune in Cape Town, arrived to inform me in both official white languages that as a trained rifleman formerly of 4SAI military battalion I was obliged to report for duty at 6 a.m sharp at the Top Star Drive-In on Tuesday, 21st March, for “special military operations”.

The letter had taken six days to reach me. I switched off Carlos Santana and grabbed a calendar. Today was the 20th.

The last time I went to the Top Star it was still the sixties. Our sixties. It was to see Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye with Maclagan in her father’s old Vauxhall Viva.

Onwards to the eighties, to Ag Pleez Deddy and to Middlemarch.

Still angry, but not yet starved with feeding.