Has the whole world gone crazy? Am I the only one around here who gives a shit about the rules?

Walter Sobchak [shouting], The Big Lebowski

The world went crazy before Rishi Sunak decided to turn the world into a perpetual Indian Summer:

…a period of unseasonably warm, dry weather that sometimes occurs in autumn in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. Several sources describe a true Indian summer as not occurring until after the first frost, or more specifically the first "killing" frost.

Wikipedia

I couldn’t resist that.

It went crazy before Ukraine, COVID, Brexit, Darfur, Afghanistan, Iraq, 9/11 and all the other cruel and crazy killing frosts, conflicts and crises of the 21st century.

We can read these events forwards, with 20th century logic, as the inevitable consequences of competing national, religious, territorial, cultural, moral, social or economic interests. Through this lens they appear to conform to the comforting historical paradigm that all conflicts are caused by rule-breakers breaking the rules of the rule-makers.

But reading them backwards, through the thick fog of epistemic uncertainty that recently got us questioning how we know what we know, we are inclined to view them rather more worryingly as the inscrutable consequences of being led down the garden path. Or several garden paths.

And since we now accept that every conspiracy theory is simply a belief system updated to explain a belief system we no longer believe in, the question de jour isn’t whether we are being paranoid or not, but rather, in the words of Hal, the not very protagonistic protagonist of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, whether we are being paranoid enough.

Those 20th century certainties crumbled into chalk-dust. So too our misguided 20th century faith in clear dividing lines between truth and lies, black and white, right and wrong, or good and evil.

Paranoia has a bad rap. It’s defined as “...an unjustified suspicion and mistrust of other people or their actions.” Or as, “...the unwarranted or delusional belief that one is being persecuted, harassed, or betrayed by others, occurring as part of a mental condition.”

It’s time we corrected that. In a world where anyone can say anything about anyone to everyone and usually will, we are justly entitled to suspect and mistrust other people and their actions. And in a climate in which so many different swathes of the global population are being persecuted, harassed and betrayed by others simply for being different, paranoia isn’t delusional, it’s vital for our very survival.

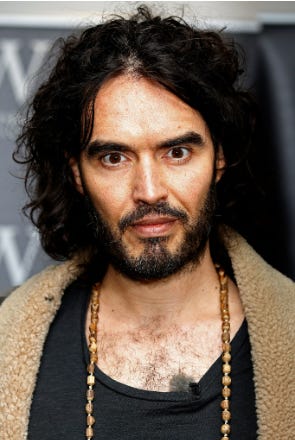

Paranoia is accused of being irrational. Which assumes that it is somehow still possible, with careful thought, clear logic and access to trusted sources of information, to arrive at a rational conclusion and a considered opinion about the motives, intentions and moral integrity of, say, Russell Brand, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Julius Malema, Lindsay Graham, the BBC and that Spanish guy who kissed the footballer.

It isn’t. And it hasn’t been since 1996. Yes, 1996 specifically.

Because 1996 was the last year we could more or less trust our brains to tell the difference between fact, fiction and fantasy.

After that, our bodies stopped believing them.

Ironically enough, 1996 was also the year that Alanis Morissette’s “Ironic” almost made it into the top ten of Billboard’s Hot Singles. Twelve years later she confessed to the London Times that she didn’t know what irony meant when she wrote it.

“Yes, I've now learnt the definition of irony — but the dictionary now says that it's a coincidence and bad luck, too.”

I quote this mind-numbingly trivial bit of trivia only because it’s emblematic of how certain we were in 1996 that we knew what we knew. And just how definitively — in the years between 1996 and the present — that epistemic carpet of rational certainty has not so slowly, but certainly very surely, been pulled from under our feet.

Simply put, we no longer know what to think.

How can I be so sure it was 1996? Here’s the thing:

Ten years ago researchers at McGill University in Montreal made an astonishing discovery that went blissfully unnoticed by everyone except the geeks around the world who pay attention to the meta-studies of the clinical trials that test for the viability and efficacy of new drugs. Since the geeks couldn’t explain it themselves, it was never very likely to make the front page of your favourite tabloid or to trend on Twitter.

To make it through a clinical trial and to get the approval required to sell it in the multi-billion dollar medicine market, a new drug has to prove that its beneficial effect is measurably superior to the effect of the placebo given to half the patients in a double-blind trial. Double-blind means that neither the patients nor the doctors administering the treatment know whether they are receiving or administering the placebo or the real thing to any individual patient. Only the statisticians in the background know who gets what.

Looking back at the data of all the trials on public record, the McGill geeks found, in the case of pain-drugs specifically, that in 1996 nearly three-quarters of patients reported pain reduction from the placebo. By 2013 it had risen to an extraordinary 91 percent. The trend predicted that around about now, in 2023, the placebo would be working significantly better than most if not all of any of the new molecules that could be produced in the labs.

The study, which obviously came as very bad news for drug companies looking to make a killing in the global pain market, has mysteriously not been followed up. Or maybe not so mysteriously.

Even more astonishingly:

The research also suggests that fake surgeries — where doctors make some incisions but don’t actually change anything — are an even stronger placebo than pills. A 2014 systematic review of surgery placebos found that the fake surgery led to improvements 75 percent of the time. In the case of surgeries to relieve pain, one meta-review found essentially no difference in outcomes between the real surgeries and the fake ones.

My italics.

You can read more of this fascinating stuff here:

https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/7/7/15792188/placebo-effect-explained

It’s where I found this wonderful quote:

One of the most successful physicians I have ever known has assured me that he used more bread pills, drops of colored water, powders of hickory ashes than of all other medicines put together. It was certainly a pious fraud.

Thomas Jefferson, 1807

I spent six or seven years of my life helping to market a clinical research organisation, entities known in the industry as CROs. The particular company I worked on behalf of had a brilliant CEO, a wonderful man who would never undertake a trial unless he could take the novel medicine himself, whatever class of drug it happened to be, before he accepted the commission. He wasn’t a doctor, but he took the Hippocratic Oath seriously and personally: First do no harm.

It’s a long way from Montreal to Kyiv. The reason I’m even daring to go there is that I don’t know what to think. I’m still clinging onto the hope that a considered, thoughtful, rational analysis will make sense of it. If I could only translate my body’s inarticulate discomfort into words. This is the story of how I did.

It’s self-evidently clear that Russia threw the first stone. Once the stones started flying backwards and forwards it became just as self-evidently clear that there was a lot of money to be made in stones.

Maybe it’s just the flower child in me but I can’t help thinking that if the tiniest fraction of the time, effort and capital that’s been going into the making, marketing and the manipulation of stones had gone into persuading the combatants to sort out their differences around a wooden table, a whole generation of kids and their families wouldn’t be dying and getting maimed in the most horrible and tragic of ways.

Hippy hopes aside, I still didn’t know what to think. Perhaps it wasn’t as black and white as it appeared. Perhaps there were degrees of nuance I simply hadn’t noticed, heard or understood. The cynicism, the paranoia and and my abject ignorance surrounding the historical and geographical context of the war had combined to numb my already limited powers of rational analysis into a state of barely sentient paralysis.

There had to be other people who were as confused as I was. I went to Google to see what kind of questions people were asking during the well-trailed, so-called, counter-offensive. Top of the list was, “Can dogs eat watermelon?”, followed by, “What channel is the war on?”

I’ve been here before. Deeply confused, I mean. Watching the BBC doesn’t usually help. This time it did.

I switched on to see Stephen Sackur, the HardTalk guy, interviewing Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina senator who is paradoxically one of the few hawks still hawking the intensification of the war against Russia in the usually and legendarily most hawkish political party on the planet.

In response to several penetrating questions from Sackur that implied that Graham was fighting a losing battle in his attempts to get other senior Republicans to get on board his hawkish mission to wipe Russia (and China while they were about it) off the face of the earth, Graham paused, very briefly, before uttering the most chilling words I’ve heard since P.W. Botha’s infamous Rubicon speech in 1985:

“We need to sell the war better.”

Several seconds before my mind was able to process the implications of those six simple words, the blood in my brain and my body had frozen in visceral shock at the sound of them.

It was at precisely at that point that I realised I was in the placebo half of the trial.

It unfroze when a sweet rush of paranoia flooded into my brain to comfort it. Stop trying to figure it out, it said. There are no good guys in this war. For the money-men, the media and the merchants of mayhem, the war itself is the good thing.

It was as painfully clear as it was clearly painful. My most deeply rooted English trait is not to trust my body. With anything.

We rewound the clip to confirm we had heard it correctly. We had. It was more worrying than I had imagined.

For a minute or two Graham elaborates his justifications for needing to sell the war better. He appears blithely unperturbed that he is advocating an even larger-scale massacre of the largely innocent.

The camera cuts back to see an equally unperturbed Sackur stroking his chin. His body language suggests something akin to scorn as Graham wanders into the muddying waters of why some American don’t want another Vietnam, Iraq or Afghanistan. At which point I can’t help imagining Sackur is restraining himself from saying something along the lines of, “You can shut up now. Why the fuck do you think I’m interviewing you if it isn’t to get you to sell the war to our 364 million worldwide viewers, you redneck moron?”

Or, as Voltaire said, “Judge a man by his questions, not by his answers.”

Later, when my mind reluctantly decided to start thinking again, I did some digging and came up with some very good reasons to reassure my body that my mind had given up its desperate search for logic, nuance or cognitive assonance:

People largely do not feel as positively about news organisations providing a different range of perspectives on the conflict. However, as the invasion continues, and as new atrocities occur daily, providing alternative perspectives is unlikely to be seen by journalists as the most pressing task.

Reuters Institute

It’s like a Hollywood movie. You have to have your bad guy, your good guy and a bunch of innocent victims and, of course, the bad guy must lose at the end.

Virgil Hawkins, Associate Professor, International Politics; Conflict Studies (Africa) and Media Studies, Osaka University, on the coverage of the Ukraine war.

They know they can trust us not to be really impartial.

Lord Reith, the founder of the BBC, describing in his diary the government’s relationship with the UK’s national broadcaster.

It is easier to fool the people than to convince them they have been fooled.

Mark Twain

War, it will be seen, is now a purely internal affair… In our own day they [the warring parties] are not fighting against one another at all. The war is waged by each ruling group against its own subjects, and the object of the war is not to make or prevent conquests of territory, but to keep the structure of society intact. The very word "war," therefore, has become misleading. It would probably be accurate to say that by becoming continuous war has ceased to exist.

George Orwell, 1984

It may with reason be said, that in the manner the English nation is represented, it signifies not where this right resides, whether in the Crown, or in the Parliament. War is the common harvest of all those who participate in the division and expenditure of public money, in all countries. It is the art of conquering at home: the object of it is an increase of revenue; and as revenue cannot be increased without taxes, a pretence must be made for expenditures. In reviewing the history of the English government, its wars and its taxes, a by-stander, not blinded by prejudice, nor warped by interest, would declare, that taxes were not raised to carry on wars, but that wars were raised to carry on taxes.

Thomas Paine, 1778

We’re fucked, Walter.

The Big Lebowski

Take your medicine and embrace your paranoia. But first and last, do no harm.

Thanks, Andy! Any mind-wrenching ideas you have would be welcome to wrench mine even more.

Good one Gor. As always. Mind wrenching though. As usual.