“It’s fine. Luckily we’re all English so no-one’s going to ask any questions. Thank you, centuries of emotional repression!” - Mark, Peep Show

*

If irony is the driest of all types of humour, England is the Alacama Desert of it, the driest place on earth. The further one travels away from it, the wetter it gets.

It is now generally agreed by all parties that one of the things the English migrants inexplicably lost overboard on their way to Plymouth Rock, the Cape of Storms, the Cook Islands, Tasmania, Ceylon, and Calcutta was their native aptitude for saying the opposite of what they actually meant in the drollest possible way.

The USA was an irony-free zone until they invented air quotes to signal that the opposite of what they meant was actually the opposite of what they meant. There’s some irony in that.

North of the 49th parallel, irony mutated into a variety of whimsical self-deprecation that has become the unmistakeable signature of Canadian humour:

Q: How do you get 26 Canadians out of a swimming pool?

A: Yell, “Everybody out of the pool!”

The Subcontinent retains a gentle, head-wobbling remnant of it.

Australians and New Zealanders replaced the cutting edge of it with the blunt instruments of sarcasm, hyperbole or both—to wit: “Nice haircut, did you get run over by a lawnmower?”

Wet, wetter, wettest.

But it’s entirely absent—almost painfully absent—from South African conversation. I can only think, in our case, that we don’t use irony because we can’t.

Stating the opposite of the truth for humorous or dramatic effect can work only when your audience shares your idea of the truth. In a country as politically fractured, culturally divided and socially complex as South Africa, the truth is a slippery, shape-shifting will-o’-the-wisp that on any given day will mean sixty million things to a thousand tribes and cultures in eleven official languages and countless unofficial dialects, not excluding Hindi, Swahili, Tamil, Urdu, German, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian and Greek.

The opposite of one person’s truth is another person’s daily reality. Try saying, “I’m dying of hunger” while examining the menu in a five-star Joburg restaurant.

From an English point of view, the consequence of the loss of irony in the former British colonies is the irksome habit colonials have of saying what they mean.

In other respects, too, the distance between the mother country and her former colonies seems to have acted as some sort of etiolating filter, as if the broad frequencies of English culture had been compressed into a very narrow band of shortwave in order for it to survive the journey across the equator. The others may have heard a stronger signal. To get to the South Africa of my youth, it had to squeeze through the Equity ban in the north and the apartheid censors in the south, arriving at last only in intermittent squeaks.

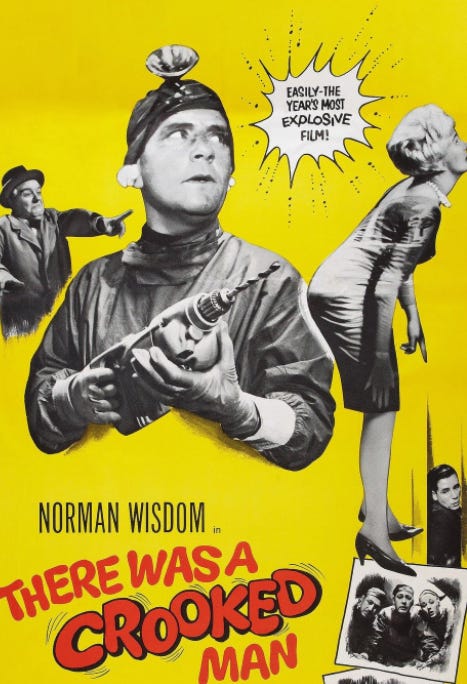

In 1976 the British actors union, Equity, banned the export and sales of all British-made television programmes to South Africa. Since television itself was illegal in South Africa until 1976, and since the last British films we remembered seeing at the bioscope at Maclin’s Café in Mooi River were The Dam Busters, Ice Cold in Alex, Carry On Up the Khyber and every single one of the twenty-six Norman Wisdom films from A Date with a Dream (1948) to What’s Good for the Goose (1969), we assumed that British television, if we ever lived to see it, would consist exclusively of black & white dramas in which soldiers with Terry-Thomas moustaches made suggestive remarks to busty women in floral frocks while shooting foreigners.

Until the Equity ban was lifted in 1993 it was easier—even under one of the world’s most draconian censorship regimes—to get a 16mm copy of Debbie Does Dallas than a bootleg VHS of an episode of EastEnders.

The disadvantage of growing up speaking English in a former British colony without television or the internet was that you got the BBC World Service but not the BBC banter—the message, in other words, but not the musings. You got the Telegraph but not the Daily Mail, the Guardian but not the Mirror. So you got the news but not the gossip, you got the language but not the nuance, you got the words but not the inflections, you got the idea but not the idiom, you got the education but not the intelligence, you got the facts but not the knowledge, you got the books but not the reviews, you got the music but not its meanings, you got the policies but not the politics.

So we got the comedy but not the humour, the images but not the picture, the concept but not the colour. We got the war but not the peace—the British but not the English.

And since the only news items we ever got to see in moving pictures were the British Pathé clips that served as trailers to the Norman Wisdom, Terry-Thomas and Hattie Jacques films at Maclin’s bioscope, we assumed that BBC television news would consist primarily of black & white footage of Queen Elizabeth II in a white floral hat waving a white-gloved hand through the glass of the half-opened back-seat window of a black Rolls-Royce to cheering crowds of exclusively white people while on her way to open a new Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, a new Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, a new Queen Elizabeth II Pier or a new Queen Elizabeth II Airport Terminal.

And since the only English people we ever actually met were our parents’ closest friends, the wonderfully eccentric and eccentrically wonderful Tom and Wendy Smith who lived on the neighbouring farm of Ivanhoe, who had left England in 1932 and who had got to Hidcote, Natal, South Africa by way of Burma, Malaya, Borneo and Ceylon, we assumed all English people of a certain class, which is to say the class of English people my mother would have approved of, were called Tom or Wendy and lived on farms named after the novels of Walter Scott, bred King Charles Spaniels, and wore wellington boots when they weren’t playing tennis or shooting guineafowl.

The effect of this on the wider English-speaking white South African population was to oblige us to contextualise the scraps of news, politics and culture that reached us from London, Manchester or Liverpool into a conception of England frozen in the period between the end of the Second World War and the beginning of cultural and sporting boycotts of the 1960s, an indelibly British, neo-Churchillian, peculiarly conservative idea of England, associated with neatly clipped moustaches, Spitfires, Just a Minute and Giles cartoons: with only Buckingham Palace standing steadfast and immutable against the fluctuating waves of taste and fashion — the mini-skirts and the Mini-Minors, the floral shirts and the bell-bottom trousers; the Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks and the Animals, the Camden hippies and the King’s Road punks.

In this context it was possible to read the very best intentions into Maggie Thatcher’s war on the unions, her adventures in the South Atlantic and her political romance with Ronald Reagan; and for some to see a sort of English boarding school justice, a polite but unavoidable detention for disobedience, in her refusal to treat the jailed Mandela as anything other than the totemic leader of terrorist cabal.

We were able to believe that we still shared the same values because both nations played cricket, even if we could no longer play each other. We thought of rugby as the lingua franca of comradeship without understanding that English rugby was played by the sons of only the most rarefied class of English gentlemen, the vestigial equivalent of sending them off to the Sudan, Lahore or Elandslaagte to make men of themselves.

My Fair Lady and Mary Poppins confirmed the illusion of a country fundamentally unchanged and unchangeable, simultaneously ante-Victorian, Victorian, and modern, still delighting in the idiosyncrasies of the classes that divided it, in that sacrosanct dispensation of entitlements and handicaps ordained long ago by a very Anglican god, the hymnal courtesy of Lonnie Donegan.

Without television and without the running commentary of the English versions of the English papers, we took what we got at face value. We knew the names of the individual Beatles but had no sense of their place in English society, by which I mean the way they viewed themselves in the context of 1960s England, and the way the various strata of English society viewed them in return. They were four mop-heads who wrote and sang great songs, and we assumed everyone in England from the Queen to my old man the dustman saw them the way we did, simply as the cuddly, mischievous boys on the cover of Please, Please Me.

The English novelists were names, not faces; not people with pasts and husbands and wives and children; not aristocrats or commoners, not individuals from this or that class related to this or that branch of royal descent or this or that twig of the haut monde or married to this or that large or small celebrity, from this or that school or university, or from this or that city or county—the names of which would anyway have meant little or nothing to us. They were authors stripped of associations, connections, and references, emerging into recognisable personalities only within the white spaces between the interstices of Monotype Baskerville.

We approached them with staggering ignorance, and we read them with the innocence of children. We made no distinction of provenance or period between Somerset Maugham and Rudyard Kipling, or between Emily Bronte and Virginia Woolf. We liked them if their stories and characters resonated with something within our range of personal experience, and we didn’t if they didn’t.

For me it meant that I could read and love W.H. Auden oblivious to his sexual preferences. I could embrace the literary theory of F.R. Leavis without knowing he had long since been superannuated into a literary joke, someone Stephen Fry would describe as a “sanctimonious prick of only parochial significance”.

So I imagined fondly that literary manuscripts in England were judged worthy of publication on the merit of the work alone rather than, say, on the notoriety of their authors and the amount of prurient gossip their names and faces generated on the front pages of the daily newspapers.

Reading a text without knowing the subtext is like watching a movie with the subtitles on and the sound turned off, which is fine if you’re watching a documentary about the climate of Greenland in Danish, but which becomes dangerously misleading when the central characters of a drama don’t mean what they say.

Until 1999 I was still certain that the disadvantages of growing up speaking English in a former British colony without British-made television programmes or the internet outweighed the advantages.

Then I got to England.

I was not so naïve as to be entirely deaf to the light-hearted, ironic nuance so characteristic of the speech of the English-born English. My mother had inherited some of it, although she tended to use it to full sardonic effect only in the afterglow of a cane or two. It shared something with the self-deprecating warmth I heard in the voice of my father, but I had a vague sense of something different in the quality of their versions, something less self-conscious, less overtly clever. Hers reminded me of Oscar Wilde and Noël Coward; his reminded me of Kipling’s Saxon who “…never means anything serious till he talks about justice and right.”

But I had no way of knowing how much of the subtext I’d been missing until I found myself living and working among the English-born English — how antiquated my father’s self-deprecation and stoic good humour would appear in 21st century Britain, nor how attenuated by time and distance had been the faint strain of irony in my mother’s voice when compared to the living, breathing, speaking thing.

Neither of my parents, not my schooling, not the books I’d read, not my Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and English Literature, not the fifth-generation VHS copies of Fawlty Towers, not even The Life of Brian watched in a huddle behind closed doors and blackout curtains for fear of the thought-police, nor anything in my experience before we came to settle in London, had prepared me for it.

The walk from Piccadilly via Dover Street to Berkeley Square, the final leg of my first regular commute, brought to mind the quaintly familiar London of Dickens. But when I found myself trying to decode the meaning of the office repartee, it felt as if I’d stumbled out of Dombey and Son and into a parody of Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies.

It was here that I realised that I didn’t understand the language I had spoken all my life. It wasn’t because of the accents. It wasn’t because I didn’t recognise the words, appreciate the irony, or admire the wit.

It was because of Dallas.

👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽

👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽