Laat elkeen sy eie hol afvee.*

Graffiti that appeared on a wall in Yeoville, Johannesburg, a few weeks before South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994.

Americans have mastered the art of living with the unacceptable.

Breyten Breytenbach

I’ve never met a woke Afrikaner. I’m not saying there are no woke Afrikaners or that there have never been any woke Afrikaners or that there will never be any woke Afrikaners. I’m just saying I’ve never met one.

I think it has something to do with Afrikaans. There is hardly a single word in the language that doesn’t sound offensive when you say it out loud.

“Goeiemôre” is literally as benign and well-meaning as “Good morning.” It can sound almost as innocuously pleasant as its English equivalent when spoken with a sweet smile by the charming assistant chemist at the Mooi River Pharmacy on a sunny Saturday morning in November. But you don’t have to go all the way down the register to a foul-mouthed Staff Sergeant at a makeshift SADF military base on the Limpopo River at a frosty 5 a.m in 1971 for it to sound like a fire-breathing imprecation from the furnace of hell cursing you and the past and future generations of your family to eternal perdition. “Goeiemôre, Meneer Torr.”

Even in the middle range of casual greetings exchanged in the streets or shops of Estcourt or Maritzburg it can sound, with its guttural G, its throaty Os and its rolled R, like a load of green phlegm being spat at your face by a completely white stranger.

“Goeiemôre.”

With the best will in the world it won’t sound woke. Which isn’t to say there aren’t any nice Afrikaners. I’ve met plenty of nice Afrikaners. They just aren’t nice in the way that English people can be nice. The word for nice in Afrikaans is lekker. It also means tasty. It’s a lip-smackingly, succulent and satisfying way of describing things that you like, whether it’s food, people, music, cars or sex. It’s carnal.

The English word nice derives, by way of delicate and precise, from from Latin nescius, meaning ignorant. To be nice is to not know. Or to not want to know. Which explains why the English find it difficult to call a spade a spade while the Afrikaners have no problem calling it a fokking shovel.

I met Breyten Breytenbach in Paris in 1974. He was nice in that lekker Afrikaans kind of way. Wokeness wasn’t a thing then. But looking back at him through the foggy lens of the present I can’t detect any signs of today’s pejorative notions of wokeness in his utterances or his demeanor no matter how hard I squint my eyes and ears to examine him through the mists of time.

But he was certainly awake to the inequities of the world in general and to the iniquities of apartheid in particular. Which is why he was in exile in France.

You may remember Breyten Breytenbach from the last verse of I’ve Never Met a Nice South African. Spitting Image referred to him thus:

He’s quite a nice South African, and he’s hardly ever killed anyone; and he’s not smelly at all, that’s why we put him in prison.

I remember a very tall, ferociously bearded and fiercely imposing man. I was twenty-one; he was thirty-five. The age difference was intimidating in itself. Even more intimidating was his reputation as South Africa’s most politically radical and controversial Afrikaans poet, his notoriety as a dangerously seditious anti-apartheid firebrand and, consequently, the terrifying idea that agents of BOSS disguised as garbage collectors or taxi-drivers in berets and tricolour neck-scarves could at this very minute be snapping mugshots of me with bowtie cameras while scribbling descriptions of my offensively long hair, my grubby brown veldskoens and my Jimmy Hendrix t-shirt in their little black books and noting me down as a Communist handlanger who would need to have that kak interrogated out of him the minute I stepped off the SAA 747 in Joburg in two weeks time. Adding to all this intimidation was the awkwardness of never having read any of his bracingly brilliant poetry.

This proved to be something of an impediment to any discourse deeper than a brief but cordial exchange of, “It’s a privilege to meet you, man”, and, “How do you like Paris then?”, and, “I’m only missing the sunshine but not the braais and the Chevrolets” as he demolished a foot long baguette handed to him by a raven-haired waitress who emerged from Ô Paris with a red, white and blue umbrella and a missing incisor.

I took from this encounter under a pavement awning on that rainy night in the rue des Envierge that not all meetings with famous people make the blindest bit of difference to the course of history, destiny, or the trajectory of one’s ignorance.

The point is that I met him, I shook his hand, we shared a beer, and in retrospect I still can't think of him as woke. His accent may have had something to do with it. And he was righteously angry — so righteously he was prepared to put his life on the line for his principles.

The following year, for reasons obscure to both me and Wikipedia, he would return to South Africa where he was immediately arrested and sentenced to nine years' imprisonment for high treason. The title of the book he wrote in prison sounds very unwoke in retrospect: “The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist”.

I looked up how albinos felt about being called albinos and found this on the website of the National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation:

In the albinism community, opinions vary on the use of the word albino. While some find it extraordinarily offensive, others feel the label carries neutral or even empowering connotations. Many people with albinism agree that their feelings depend on the context or intent in which the word is used.

So yes and no. But I have a feeling Breytenbach wouldn’t have cared either way.

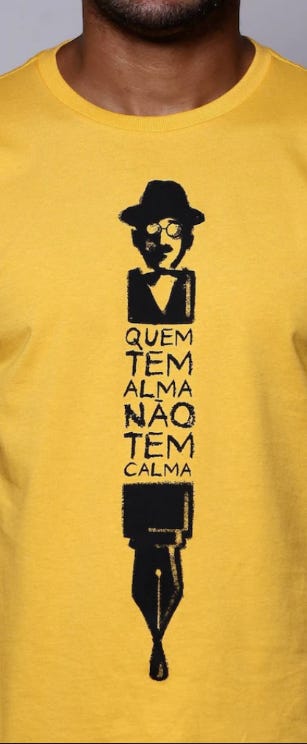

Artists, poets and musicians are generally thought of as woke. Stereotypically they tend to be as temperamentally sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of others as they are to the restless daemons of their own introspections. And empathy with people unlike ourselves must surely be the very essence of wokeness. No one, to my knowledge, has expressed this reading of it as succinctly and as memorably as Fernando Pessoa: “Quem tem alma não tem calma” — which translates loosely as, “Whoever has a soul will never have peace.”

This conception of artistic wokeness, which we appear to have inherited from the English Romantics of the early 19th century, has long outlived the validity and relevance of the anti-industrial cliches that spawned it. But the history of its persistence is extraordinary, especially in England, in the British colonies, and in the English idea of the requirements for artistic expression that I and many of my English-speaking South African contemporaries inherited from the same tradition.

The First World War should have killed it. Instead it gave us woke and whiny war poets like Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brooke. It survived the Roaring Twenties to re-emerge in the forms of John Betjeman and T.S. Eliot. W.H. Auden did his best to rebel against it but he was no match for Vera Lynn, the saccharine sweetheart who buried the atrocities of WW2 under a coat of sugar so deep my father couldn’t talk about the war without breaking into We’ll Meet Again or Roll Out the Barrel. And he had witnessed them.

It would have survived the fifties if it hadn't been for Elvis.

Yes, I know. It’s hard to say it but without Elvis we wouldn’t have had rock 'n' roll. And if we had never had rock 'n' roll we’d still be thinking that poetry should be about spring daisies, and novels should be about finding true love, and that the only artists worth paying attention to would be those who know how the late afternoon light falls on haystacks in a Gloucestershire field in autumn.

And if Elvis hadn’t outraged so many southern state Christians by moving his hips quite as suggestively as he did, we probably wouldn’t have the right to do and say and shout out loud the most outrageously offensive things we ever imagined to anyone who cared to listen or not.

We wouldn’t have Basquiat, Bukowski, Bobbi Starr or Breyten Breytenbach. We wouldn’t have had Lolita, Satanic Verses or A Clockwork Orange. We wouldn’t have had Andy Warhol or Andres Serrano. More pertinently, we wouldn’t have Die Antwoord.

If you’ve never heard or never heard of South Africa’s most successful musical export since Dave Matthews this will give you a flavour:

When I'm on the mic it's like murder murder murder!

Kill kill kill!

Wat se Suid-Afrika?

Suig my fokken piel

Hier kom ek weer

Like a lekker a smack in the face

Rappers are fokking pouring into passenger planes

What happened to all the cool rappers from back in the day?

Now all these rappers sound exactly the same

It's like one big inbred fuck-fest

Sies

No, I do not want to stop, collaborate or listen

Anri du Toit (born 1984), known professionally as Yolandi Visser, has taken the guttural offensiveness natural to Afrikaans (and much of South African English) and combined it with the most anti-woke sentiments you never thought you’d ever imagine to become a world-wide phenomenon. When I say “world-wide” I mean all those parts of the world that are sick of being told to wake up to woke. They include the same southern American states, the Eastern European goths and, well, Australia.

I’m not judging. I like it that it’s out there whether I like it or not. If we can’t imagine how the world looks to someone we violently disagree with, violence will follow as inevitably as the Proud Boys followed Trump.

The Calvinist Afrikaner and the Southern Baptist have a lot in common. Not for them the gentle New Testament Jesus of charity, love and tolerance. They prefer the wrathful, vengeful, blood-and-thunder of the God of Deuteronomy who gave explicit instructions for the genocide of the Hittites and the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Lebusites to make way for the Chosen.

It occurs to me now, musing along these lines, that God must surely have sent his only-begotten into the world to woke-wash his very unwoke reputation.

The Baptists saw Elvis the way the Afrikaners saw Elvis, i.e. with all four of the four kinds of disgust. They viewed the rights of the darker races the way the Afrikaners viewed the rights of people darker than themselves, i.e., dimly. And both parties liked and continue to like country music as much as they like and liked raw meat smoked by a very smoky coal fire. Or, as Yolandi would say, like one inbred fuck-fest.

But southern state Americans and white conservative South Africans, especially the Afrikaners, also share the same rugged, frontier spirit that Emerson describes in Self-Reliance, his 1841 essay that would become the spiritual manifesto of today’s Republicans.

As the next general election looms large on the horizon of the hopes and dreams of South Africans longing for a government who will know how to turn the lights back on, the same Emersonian sentiment has found voice in the phrase, “Ek sal dit doen” — I’ll do it myself.

It may be anti-democratic but, as Pierre de Vos explains so empathetically in The Daily Maverick, it is also entirely understandable.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-08-31-lets-pray-that-voting-in-sas-2024-elections-doesnt-feel-like-the-triumph-of-hope-over-experience/

The anti-wokeness shared between rednecks and anti-rooinekke occurred to me most vividly a few years ago when Brer Andy told me about “the potato guy”. Angus Buchan, a desperately indigent white farmer from Zambia, planted his life’s saving’s worth of potatoes in a dusty field somewhere in the Free State. He was warned by his neighbors that nothing could possibly grow there. Nothing ever had.

He prayed and waited; he waited and prayed.

It could have been his prayers or it could have been that he had bought the growable kind of potato seedlings. When they not only grew but flourished, he chose the Jesus explanation. On the latter’s behalf he went on to write a best-selling book called Faith Like Potatoes, and to proselytize his miracle to packed stadiums of mostly white male Afrikaners who trekked to get there as though it was 1836 all over again. When a million of them gathered to hear him speak in Bloemfontein, I was inspired to write a song about it. It’s attached here for your amusement.

Lekker, ne?

*Let each one wipe his or her own asshole.