You couldn’t see Lowlands from the R103. There was just that isolated road sign pointing to the left where regions of empty veld stretched into the grey smudge of the Drakensberg’s Injisuti Dome on the distant horizon. And since we had never heard of anyone who had been to Lowlands or come from Lowlands, and since it was the last road sign we saw as the R103 swept down past Fort Durnford and the Eskort Bacon Factory before crossing the Bushman’s River, its name came to suggest the existence of a mythical hell-hole even more hellish than Estcourt, as if to reassure us that things couldn’t get worse if we pressed straight ahead.

It’s not the fault of Estcourt, the town. There is no evidence to suggest it was populated in the mid-sixties by more paedophiles, predators, paederasts and sadists per head of population than any other town or city between Agulhas and Zeerust.

But take a society in a former British colony divided at the time by the politics of racial hatred and white supremacy; now select only the white pre-adolescents and adolescents irrespective of their language and their familial cultures, remove them from their natural habitats where parental authority had some constraining effect on their pre-adolescent confusions and their adolescent urges, mix them together in an institution modelled on an educational system founded in England by Bishop William of Wykeham in 1382, situate it on the geographical fault-line that divided history’s white losers from history’s white winners; equip their teachers, young, old, male and female, with a carte blanche of grotesquely imaginative ways of punishing naughty children, and with rattan canes and an unlimited licence to abuse, molest and torment, and you’ll have just some of the ingredients that went into the making of the toxic brew of incontinent concupiscence that bubbled within the designated boundaries of the boarding schools of Estcourt when all the day-scholars had returned to the comforting bosoms of their families and their cosy dinners of cottage pie and custard apples after hockey and rugby practice and the black gates had closed behind them.

It was Oh, Lucky Man without the lucky; it was Spotlight without the light; it was Leaving Neverland without the leaving.

One at a time.

I began with the way the landscape changed between Mooi River and Estcourt because geography exists long before history begins. The Giant of the Drakensberg had been lying on his back and watching the revolving diorama of the heavens for uncountable millennia before the constellations in the night sky shifted into the configurations we saw above Drakesleigh in those days: Orion and his belt above the front lawn, the Pleiades over the tennis court, the Southern Cross above the silhouettes of the tool-shed and the plum trees when you stepped out of the kitchen door; the rest of them like diamonds scattered on black felt as if to say there were more of them than men could steal in a century.

Geography gave way to history after two or three trips to Estcourt Junior School and back again for occasional long-weekends, for Easter hols, and for mid-term breaks.

We would come to think of it later as a journey from the sweetness and light of the farm’s endless freedoms into the glowering depths of a darkness we felt in the chills of our skins and the shivers in our spines, but which we couldn’t understand or share, not even with one another, because we didn’t have the words to describe it, nor the names to call it what it was.

Helen was seven and I was ten. So at first we thought of it and spoke about it only as journey from the familiar to the foreign, from our cosy English comforts to the cruel vicissitudes of an ongoing war between creeds and cultures, a clash of civilisations that continued to pit the descendants of the British settlers against the descendants of the Afrikaner Voortrekkers — a white kids’ war, to paraphrase Conan Doyle, enacted between two irreconcilable enemies in pinches and punches in the playground, and behind our backs or in our faces with foul looks and a fouler vocabulary.

From all the men of many hues who make up the British Empire, from Hindoo Rajahs, from West African Houssas, from Malay police, from Western Indians, there came offers of service. But this was to be a white man's war, and if the British could not work out their own salvation then it were well that empire should pass from such a race.

The Great Boer War - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1899/1900)

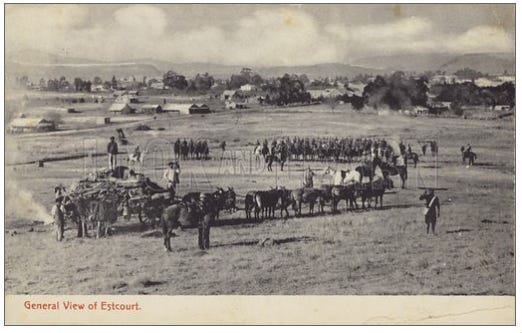

One of the legacies of the Boer War was to situate Estcourt on the geographical and cultural frontline that divided the largely English-speaking white south of Natal from the largely Afrikaans-speaking white north of Natal, making Estcourt, in effect, the northernmost outpost of the Last Outpost of the British Empire.

Both boarding schools were consequently bi-cultural. I hesitate to say bilingual because, even though we were obliged by the state to be taught Afrikaans in formal lessons five or six times a week, we tried hard not to understand it. Following the example set by my mother and all the other mothers of English-speaking Natal at the time, we certainly never deigned to speak it. The Afrikaner kids, by contrast, would all learn to understand English and would speak it when necessary, if only and always through gritted teeth as though they were spitting out indigestible and unnameable chunks of gristle regurgitated from the pits of their churning acid guts and enjoying the relief of it.

In our favour, numerically if not historically, the English-speaking boys and girls outnumbered their Afrikaner counterparts in proportion to the British and Boer losses in the two Boer Wars, which was nothing to be particularly proud of from a British (read: English-speaking white South African) point of view.

The Treaty of Vereeniging had ended the war but not the mutual contempt of one side for the other. It was expressed most memorably and vividly in crude insults and racist slurs, the Afrikaners conclusively winning the battle of crudeness, the English usually winning the battle of racist denigration.

So we, the English, called them hairy-backs and rock-spiders, unconsciously echoing the Victorian literary tropes of English racial superiority and the fears of infection, miscegenation and genetic dilution posed by mixing with an inferior racial type.

Several degrees more inventively, they called us soutpiele, or just souties for short. Sout piel translates literally as salt penis, the idea being that English-speaking South Africans had (and still have) one foot in England and one foot in South Africa. It requires some imaginative effort to see the consequence: a Colossus in mid-stride, his colossal dick distally submerged beneath the salty waves of the Atlantic Ocean. But once you see it, it’s impossible to un-see.

They also called us rooineks (rednecks) because the early British settlers took a while to learn that only the broad-brimmed hats of the Afrikaners could prevent their pale necks from roasting red in the South African sun. And they called us kaffirboeties (brothers of the blacks) because they thought, mistakenly, that we all quite naturally sympathised with the plight of our darker-skinned fellow South Africans just because Helen Suzman, the lone anti-apartheid voice in our all-white parliament, did.

You were damned if you took it as a compliment. You were doubly damned if you took it as an insult.

Whingeing pom doesn’t even come close.

So we called them Dutchmen on the assumption that reminding them of their European provenance was the most damning of all possible insults, which is not unlike the way English Brexiters will damn white uitlanders in post-Brexit Britain today by calling them Frenchmen, or Germans as the case may be, the dismissive disdain italicized by the tone of voice.

All of that was background noise, the ridiculous and predictable fallout from the history of South African politics and the politics of South African history, not to be examined, challenged or debated. It was a shadow, a persisting smell, a fact of life.

But there were other taunts and epithets a lot more explicit and a lot less imaginative than that. Unfortunately for Helen, me and the other English kids who had grown up with Robin Hood, Peter Pan and Winnie-the-Pooh, we ran out of unsavoury expletives and stinging obscenities long before the Afrikaners did.

Or fortunately.

It’s strange to have to admit it now, but in the end those crude Afrikaner expletives were also illuminatingly educational — possibly even sanity-saving.

In the eyes and ears of a child, things that don’t have words to name them don’t exist. You might have seen them, smelled them and touched them with your fingers, but without words to describe them they appear in your consciousness only as uncomfortable fictions no one ever put in a book or drew a picture of. They are there without being there; they are present without a presence. They’re like the dreams you never could and never would share with your siblings or your parents because you knew you had imagined them. And you knew you shouldn’t have imagined them.

The grandsons and granddaughters of the Boers had words for everything. And they had no compunctions about saying them out loud, describing them in graphic detail, or illustrating them with pen-knives in the doors of toilet cubicles, or with soft orange shale on the crumbling stone walls inside Fort Durnford.

There is an unfathomably deep irony in this. Fort Dunford, now beautifully restored, was named after the quintessentially English town of Durnford:

“…a civil parish in Wiltshire, England, between Salisbury and Amesbury. It lies in the Woodford Valley and is bounded to the west by the Salisbury Avon and to the east by the A345 Salisbury-Amesbury road. The parish church and Little Durnford Manor are Grade I listed.” - Wikipedia

That I should have learned almost everything I would ever learn about the birds and the bees from the crude anatomical drawings, annotated in Afrikaans, on the walls of a fort purpose-built to defend the British from the Zulus and to resist the Boer advance into southern Natal, and named so benignly after such a perfectly proper English parish, is, well, irony with knobs on.

But without the endlessly rich and informative sexual and scatological vocabulary we learned from the Afrikaners, without the words that reified the uncomfortable fictions that couldn’t be talked about in a polite English family, we may have succumbed more readily to the invitations to forbidden intimacies that would soon be whispered in our ears by hostel masters and mistresses with beer and whisky breaths waking us up with sweaty palms in our Estcourt boarding school dormitories in the dark vales of midnight. The worst of them came with Jesus on their lips.

I can forgive the regular and brutal lashings, the degrading fagging, the ritual humiliations, the Spartan regime, the food fit only for animals, the endlessly awful evenings of prep and more prep, and the endlessly dreadful nights of internment. I can’t and won’t forgive the cynical exploitation of what little innocence hadn’t been beaten out of us. So I’m going to say this once, then I’ll move on.

At Estcourt High School in 1966 or 1967, I was asked to testify at an inquiry investigating accusations by two of my fellow-pupils involving sexual abuse by a resident hostel master that had allegedly occurred at Estcourt Junior School in 1964 and 1965, and perhaps earlier. For obvious reasons I will reveal neither the name of the accused nor the names of the accusers. Nor will I reveal what I saw or what I said. The accused, in the meantime, had left the town and, possibly, the country. I was never apprised of the outcome.

I would have trusted them to deal with it appropriately and take the steps necessary to ensure it wouldn’t happen again if the teacher appointed to head the inquiry hadn’t himself, under a cloud of accusations regarding his own sexual propriety, been obliged to leave the town, and possibly the country, a few years later.

So it’s with no respect whatsoever to the staff of Estcourt Junior School and Estcourt High School who had anything at all to do with the supervision of those hostels in the period between 1963 and 1969, no matter how well-intentioned, how nice or how professional the majority of them may have been, that I now publicly accuse them all of a gross dereliction of the fundamental duty of care they owed to the boys and girls who had been placed in their guardianship.

If they didn’t know what was going on they were either wilfully blind or unforgivably stupid.

If they did know, they were complicit.

When good people say nothing, bad people can do anything. And they will.