Ag pleez Deddy won't you take us off to Durban

It's only eight hours in the Chev-Ro-Lay

There's spans of sea an' sand an' sun

And fish in the aquari-yum

That's a lekker place for a holi-day

Jeremy Taylor, “Ag Pleez Deddy”,

Durban has been a pioneer of what is called, in extremer forms, municipal socialism, and enjoys the reputation of being the best managed and most progressive town in all South Africa.

James Bryce, Impressions of South Africa, 1895.

It’s an entirely inconsequential but nevertheless a freakishly extraordinary historical fact that Mahatma Gandhi, aged twenty-nine, Mark Twain, aged sixty-three, my maternal grandfather Leyland Benjamin Smith, aged five, together with seventy-two of the most important poets of the 20th century, were all in Durban in 1896.

Winston Churchill would arrive in the city three years later, aged twenty-six.

Gandhi was making a nuisance of himself as an upstart lawyer demanding local government representation for Durban’s rapidly burgeoning and infamously disenfranchised Indian community. Mark Twain was on a wildly popular lecture tour promoting his wildly popular tales of Mississippi boyhood. My grandfather was polishing his first pair of school shoes.

Churchill would be attracted by the nascent smell of Boer blood in the Highveld air.

It was a matter of time. The vultures of Empire had long been circling over the gleaming reefs of Transvaal gold and eyeing the glittering seams of Kimberley diamonds. War with the Boers was simply a question of finding and polishing a suitable apple of discord they could hand to the compliant English press and sell to the unimaginative Little Englanders in the House of Commons.

The seventy-two poets were the inventions of Fernando Pessoa, aged ten, then studying at St Joseph’s Primary School on the corner of West Street and Broad Street, currently graced by Durban Boxer Superstores.

Not least for the scores of heteronyms he fabricated to write poetry on behalf of his many literary alter-egos, Pessoa is regarded as one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century, and as one of the greatest poets in the Portuguese language.

He had sailed to South Africa with his mother in early 1896 to join his stepfather, João Miguel dos Santos Rosa, a military officer who had been appointed Portuguese consul in Durban.

In 1899 Fernando graduated from St Joseph’s to Durban High School. The family would spend a year back in Lisbon between August 1901 and September 1902 before returning to DHS where the Portuguese prodigy continued to amaze his teachers by the fluency in English and the elegance of the poetry he employed it to produce. The English essay he wrote for his entrance examination to the University of Good Hope, now UCT, won him the Queen Victoria Prize in November 1903, beating 898 candidates.

History does not record whether Fernando Pessoa or Leyland Benjamin Smith attended any of Mark Twain’s Durban lectures, or whether Benjamin and Fernando caught a glimpse of one another strolling with their parents on the Esplanade or paddling in the warm Indian Ocean waves of Durban’s South Beach.

Pessoa’s most forensic biographer, Richard Zenith, suggests that he may have attended one of Mark Twain’s “At Home” gatherings for schoolkids, and that he may even have been inspired to invent his pantheon of alter-poets after hearing that Samuel Clemens had changed his name to “Mark Twain”, steamship-speak for, “Beware, only two fathoms deep!”

We know that Gandhi and Churchill, who for fifty years would find themselves implacably opposed to each other regarding the practices and legacies of the British Empire, would meet in person only once, in London in November 1906, when Churchill was the Undersecretary of State for the Colonies and Gandhi was petitioning the British government to recognise the rights of his Indian countrymen in South Africa.

But according to historian Arthur Herman they may well have crossed paths on the Boer War battlefield.

Gandhi had signed up as a stretcher-bearer in the Indian Ambulance Corps. Churchill was a young reporter who had been commissioned as a second lieutenant for the South African Light Horse. Gandhi was carrying the wounded General Woodgate out of the bloody chaos that was the Battle of Spion Kop. Churchill apparently observed the incident from only a few yards away. And apparently with sublime equanimity.

The Kop stand at Anfield, built in 1906, would be named for the hundreds of soldiers from Lancashire who died in the Boers’ most celebrated victory.

I made up the “sublime equanimity” part. We don’t know how Churchill viewed the incident at Spion Kop, but the clues suggesting his casual indifference to the suffering of others were apparent long before his infamous remark in response to the death of some three million people in the Bengal famine of 1943, for which Britain’s economic policies were largely to blame, viz:

“I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.”

Earlier, when he became aware of Gandhi’s anti-colonial sentiments and his growing political influence in India, Churchill would describe Gandhi as “a malignant subversive fanatic”, and mock him as, “...a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal palace.”

The clues were there even earlier than that. And, as fate would have it, it was Mark Twain who would call them out.

Churchill had missed meeting Mark Twain on the latter’s Durban lecture tour in 1896, but their paths crossed four years later, in December 1900.

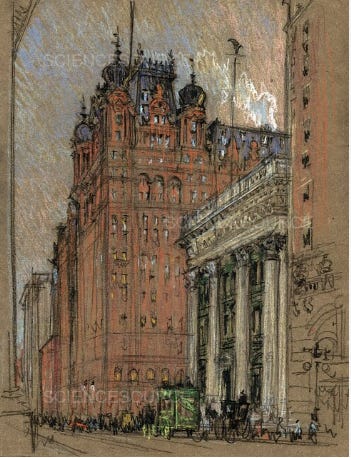

The venue was the Ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria in New York City. And this time it would be the swashbuckling Churchill on the podium, fresh from his romp through the battlefields of the Boer War, during which eight months of his action-packed Boy’s Own adventure he had witnessed Spion Kop, been captured by the Boers, escaped from the Boers, and undertaken a gruelling 400 mile journey on foot through terrifying Zulu country to get back to Durban where he was greeted by hugely orchestrated crowds of adoring white English colonists, Benjamin and the Smiths among them.

Twain’s disdain is palpable in Salon magazine’s account of their meeting:

The twenty-six-year-old celebrated British war correspondent was on a lecture tour, picking up handsome fees to talk about his bloody adventures and headline-grabbing writings on imperial conflicts around the globe. By contrast, Twain, at age sixty-five, loathed the chest-beating of war—especially the jingoistic, romanticized accounts of farm boys ground up and left for dead on the battlefield. Twain feared his nation might someday become an empire like Great Britain.

Twain made plain how wrongheaded Churchill had been about the British Empire pestering those poor indigent people in places like India and South Africa. Churchill “knew all about war and nothing about peace,” Twain told the standing-room-only audience, many of whom seemed to agree with him. As an account of the evening by the New York Times explained, “War might be very interesting to persons who like that sort of entertainment, but he [Twain] never enjoyed it himself.”

Thomas Maier, Salon

The famous Churchill Capture Site is situated just north of Estcourt, a few miles from the non-existent town of Frere. In those days it was just a slate of marble on a pile of bricks in a ditch on the side of the road.

Every time we passed it on the way to Colenso, Ladysmith or further north, my mother would say, “That’s where the ghastly Boers captured our beloved Winston.”

My father would smile. “No, dear,” he would say. “That’s where he jumped from the train and ran back to Durban when he heard the first shot.”

That’s what the boys had told him in Italy in 1944. My mother said they were probably just as bitter as the cold.

I never knew who or what to believe. But it wouldn’t have been the first time the authors of the history of the British Empire polished the first draft of it to make it reflect more kindly on the present.

The most hilariously blatant, terribly tragic and notoriously expedient example took place in March, 1917, when the loyal British subjects of the regency of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha found themselves being bombed by the Gotha G.IV, a German heavy aircraft capable of crossing the English Channel.

After a hastily assembled brainstorm among those responsible for picking the nastiest bones out truth out of the Empire’s hearty broth of factually wholesome beneficence, George V was obliged to declare to the nation that all descendants of Queen Victoria in the male line who were also British subjects would henceforth be adopting the surname Windsor, the well-established name of the eponymous 11th century Norman castle in Berkshire.

George didn’t mention the Norman part.

Since the name Windsor meant only windy hillside in Ye Olde English and had no glorious British history to speak of, and since none could be invented on the spur of the moment, urgent cables were sent to all the Anglo colonies past and present to persuade as many of their cities and town as could be persuaded by carrot or stick to change their names to Windsor. Today there are thirty-two of them, some, admittedly, vestiges of British settlement in the US before 4th July, 1776.

It was a brilliant as it was cynical. In years to come it would look as thought they had been there forever. The Windsors. Yea, truly, Napoleon was right. “History is an agreed upon set of lies.”

Peculiar footnote:

The Whitehall wonks must have had the idea in their locker for some time. In 1850 a new township was proclaimed only fifteen miles from what would become known as the Churchill Capture Site. They called it Windsor. But it wouldn’t be long before Durban’s pesky Anglicans named it Colenso after their favourite Bishop.

“I feel as if I'm always on the verge of waking up.”

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet