When television eventually arrived in South Africa in 1976 it came in the form of one official channel divided into equal time-slots of Afrikaans and English. Six years later the SABC would introduce TV2, broadcasting in Zulu and Xhosa, and TV3, broadcasting in Sotho and Tswana. Before the Equity ban on the sale of British programming to South Africa came into full effect, South Africans were treated to a strange and eclectic mix of entertainments.

The Sweeney, that ground-breaking police drama set in a very cockney London, squeezed through a legal loophole by being dubbed into Afrikaans and called Blitspatrollie (Rapid Patrol). Miami Vice became Misdaad in Miami (Crime in Miami), The Six Million Dollar Man became Die Man van Staal (The Man of Steel) and The Jeffersons, those former neighbours of Archie and Edith Bunker, became a Zulu-speaking family with a dry-cleaning business in the heart of Manhattan.

If your Afrikaans couldn’t keep up with Detective Inspector Jack Regan and Detective Sergeant George Carter, and if your Zulu wasn’t good enough for you to relish the banter between George and Louise Jefferson, there was only one option left: you watched Dallas.

You watched it with reverence, you watched it in awe. You watched it for thirteen years, and you watched it long after the entire planet knew who shot J.R. and how Bobby arose from the dead. You watched it so assiduously and with such close intent that the politics of the Texan oil industry began to feel more demanding of your attention than the politics outside your front door.

Suddenly, and quite arbitrarily, the Anglo-Saxon cultural stream that had come to rest in the quiet mill-pond of the Natal Midlands was diverted into the rapids of the lower Colorado. My father exchanged his slouch hat for a Stetson; my mother arrived at the view that Miss Ellie hadn’t been firm enough with her children.

And all the while we were analysing Sue Ellen’s moral laxity on the veranda of Drakesleigh, the writers and producers at the forefront of English television were laying siege to middle-class complacencies, hunting down the last of Victoria’s holy cows, and inventing a new, post-punk, post-modern, post-ironic culture of iconoclasm that was both radically fresh and desperately self-regarding. Coronation Street and EastEnders had continued to reassure the same middle-class that nothing in England had changed since Edward VII. But we discovered when we switched on the TV in the flat in Fulham in 2000 that the originality of Fawlty Towers had given way in the 1980s and 1990s to an impenetrable self-referential surrealism that would soon hypostatize into the unapologetic neo-Orwellian cynicism of Big Brother.

I would piece this together only in retrospect, and then only by amateur deduction and uneducated conjecture. But even if we hadn’t been cut off from British television and the way it was reflecting the changing tastes of its audience in the UK, I’m not sure that I would have paid much attention to it. By the end of the 1970s, certainly no later than the December of 1980, I was no longer looking to England to satisfy my appetite for the cultural titbits denied us by our self-inflicted status as the least touchable of the pariah nations of the world.

Today Professor Nigel Penn is a globally recognised expert on the Dutch and British colonial genocides in Africa, Australia and elsewhere. In the early 1970’s he was just Nigel, Helen’s very complicated boyfriend, who read much more than was good for him—or maybe not, the way things turned out.

We were at a braai in the garden of a house in a suburb of Johannesburg, one of those hot and lazy days next to a blue swimming pool with the Kreepy-Krauly chugging its lonely path up and down the fibreglass walls, rising every now and then to splutter and burp on the surface before submerging again to its Sisyphean labour against the inevitability of algae. We gave our bones to the obligatory Doberman and he gave me a copy of Gravity’s Rainbow.

Thomas Pynchon led me by way of Nabokov and Vonnegut to John Barth, William Gaddis, De Lillo and the rest of the American school now known as “the hysterical realists”. I wondered if it was only a coincidence that I was reading Gaddis’s JR at just about the time J.R. was roasting Cliff Barnes with his excoriating wit:

“The only thing that is screwed up in this office, Barnes, is your head, which I would be more than happy to serve on a silver platter if I weren’t worried about my family getting food poisoning!” — J.R. Ewing, Dallas

High culture, low culture - it hardly mattered. I had discovered the new America and I wasn’t going to look back. I imagined Pynchon’s Tyrone Slothrop watching the last train pulling out of Waterloo Station and seeing the pale-faced ghost of Phineas Finn in a carriage window looking out in bewilderment at the smoking ruins of Vauxhall. It seemed to me then that the American cultural conquest of South Africa had also vanquished and occupied the place in my mind once populated by Anthony Trollope, Anthony Powell and the Allahakbarries.

Consequently, in the interval between my first brief visit to London in 1974 and my first day at the office in Berkeley Square, familiar words had acquired unfamiliar meanings. They had resonances I was deaf to, and implications I was blind to. In 1976 I could read Clive James’s Crystal Bucket and appreciate his droll take on British television shows I had never seen. Twenty-three years later the reviews in Time Out appeared to have been written in the language of alien conquerors from a distant galaxy.

The cockneys had apparently been wiped from the face of the earth. In their place on the streets of Hackney and Harrow were kids in hoodies speaking an unknown patois into portable telephones. Instead of the obligatory black, the creative classes in Soho, Farrington and Islington were wearing the kind of shirts my mother made us wear back in the fifties, and they were talking in riddles that weren’t from Beano. In the South West postcodes I was reassured to hear an occasional “awfully kind” or “terribly nice” that wouldn’t have been out of place in Nottingham Road, Kwa-Zulu Natal. But this charming English habit of inverting the meaning of words seemed to have spread through the dictionary the way the bur oak blight spread through the forests of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire.

I was pleased to be told that an idea of mine was “worthy” until I discovered to my bewilderment and shame that the word was commonly understood to be among the worst of all possible advertising insults.

I learned that “good” meant irredeemably awful. Anything described as “fun” needed to be avoided at all costs. I learned that “nice” had lost its 20th century meaning of “moderately pleasing” and had reverted to its original sense of appropriateness, but now with an ironic exclamation mark, as in the phrase, “How inadvertently apposite!”

The word “brilliant” was loaded with the implication of something unspeakably moronic. “Lovely” covered all the shades of meaning on the spectrum between almost bearable and unbearable. All words relating to abstract ideals such as sincerity, fairness, faith, honour, and glory had been hollowed out as if by a scalpel, and relegated to the domains of hunting, shooting, fishing cricket and rugby. But none of these imputed meanings were fixed. They could change with changing contexts and changing circumstances, as predictably as the weather.

Even now it remains peculiarly difficult to describe because the graduated shades of its expression appear to be bound up with those fine gradations of English class that are so obscure to the rest of us. It sounds like innuendo to the foreigner but it’s several degrees less crass than that. It’s far smarter, far more layered, and far more subtle. There’s a self-directed ridicule about it that chafes at earnestness and mocks its own mannerisms. It has a way of puncturing pretence and poking fun at high-mindedness that makes words such as liberty and fraternity sound rude and inappropriate, like boorish gate-crashers at a Wimbledon garden party, probably South Africans.

It’s not the heavy-handed irony we colonials use to score crude political points. It’s a dry, jocular disingenuousness gently and consistently undermining the overt meaning of the casual exchanges between the English-born English. At its sparkling best it is humane and inclusive: it’s Stephen Fry (again), Ian Hislop and Paul Merton. It’s a little bit of Russell Brand and a lot of Jonathan Agnew, the cricket commentator. It’s the cabbie pointing out London’s landmarks for the benefit of the foreigner in the backseat: “That’s Lord’s,” he said, directing my attention to the large building on my left, “the home of some of England’s most famous defeats.”

At its worst it is self-referential and excluding of others, a circular conversation that refers back to the punchline of a joke that we weren’t privy to and wouldn’t have understood even if we were, because that punchline was a reference to the punchline of an earlier joke, and so on and so forth in a hermeneutic labyrinth that has the effect of making English disingenuousness itself sound disingenuous to the baffled ears of outsiders, like two enigmatic negatives making a puzzling positive.

But “joke” is too strong a word. The colonials have jokes, the English have witticisms.

It took me more than a year or two to realise that the point of English conversation was to gloss over difficult subjects as amusingly as possible, and never, under pain of excommunication, to address them in earnest.

There was that famous dinner party with newly-made friends at their gracious home in Putney. We didn’t know that you weren’t supposed to ask people what they did. When the husband replied politely that he worked in “the city” I thought he meant in London so I said, “So do I”.

Eventually I would learn to hear the commas, the dashes, the semi-colons, the full stops and the question marks in crisply spoken English speech. But never the capitals.

They were nice enough to make light of our colonial ignorance. We navigated our way to the safer shores of children, schools, and foreign holidays. Things were going swimmingly until we ran out of things to say about the English climate. Karine broke the strained silence over the Eton Mess by informing our astonished hosts that the stem cells of a baby boy’s foreskin could be grown to cover the width and breadth of a rugby field.

I would gather later from nods and winks around the water-cooler that it wasn’t only the foreskin that had offended them. The English won’t and don’t talk about matters sexual, let alone sex itself. The physical act of it is apparently reserved for Friday nights only. Then they indulge in it less in passion than in relief, as if it’s the denouement of a risqué shaggy-dog story they’ve been hinting at in suggestive smirks since Wednesday afternoon.

We could blame it all on the Victorians, Winnie-the-Pooh and Mary Whitehouse if 336 lines of Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet (c.1595) weren’t still expurgated from the standard English text in, yes, 2022.

The hit comedy of 1973, No Sex Please, We're British, turned out to have been a documentary.

Like everything else in life with the capacity to stir the blood, whether they’re the loftiest political ideals or the basest bodily gratifications, sex in England has been reduced to one among many of those naughty little thoughts that are excusable only because children can’t help having them.

Karine never got used to English reticence the way I did. I liked it that no one spoke on the train, not to each other and not to me. She continues to strike up conversations on the Bakerloo Line with strangers who hide behind the sports pages to avoid her puppy-like solicitations.

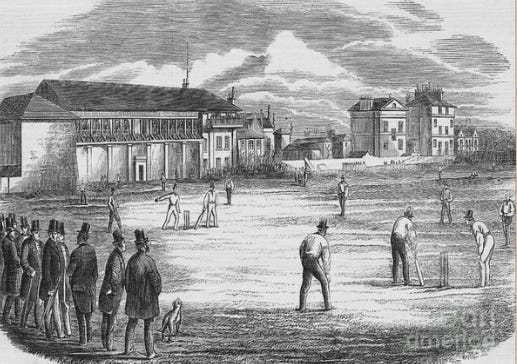

But I grew to love the office banter and cocktail party chit-chat. I admired its quick-wittedness, its playfulness, and its delicious seditiousness. I began to see the world through their kaleidoscope of fanciful inversions: that peculiarly English filter that reduces a global cataclysm to the scale of a cricket match on a village green while amplifying The Ashes to the scale of a war between continents.

It turned out that English wit could equally be used as a double-edged sword to intimidate by its cleverness, the way Boris Johnson and his ilk wield it to disrespect the intelligence and demean the opinions of those who disagree with him or those who are of a class beneath him, viz: the same people, by definition. Then it’s obnoxious or worse.

Saying the opposite of what you mean is only amusing if you don’t mean it. A mischievous subversion of the obvious can slip almost unnoticed into a cynical misrepresentation of the facts. From there it’s only a hop and a skip to outright mendacity, and thence to a cancerous corrosion of trust in all forms of political and social discourse.

This is no longer the conjecture it was at the time of writing in 2017.

Not all of the English are as cynical as the governments they keep electing. But glossing over the hard truths with amusing half-truths is the default position of many—a quirk, an oddity, an English trait, a natural reflex of the national consciousness. Or it could be deeper, perhaps the instinct of the collective unconscious of a nation never humiliated by a defeat on its own soil, and never disgraced at home by its actions abroad except in the eyes of the small minority Arthur Conan Doyle called “the pusillanimous few”, those Little Englanders made cowards by Britain’s might.

I was conscious of its artificiality, conscious of my skin thickening against the penetration of guilt or responsibility for the suffering of those outside my magic circle. It was a process of moral numbing as welcome as anaesthesia to a skin chafed too long by shame and regret, but I was happy to acquiesce to the unusual comfort of it, the unanticipated relief of not having to care very much about what happened at the wrong end of the telescope.

South Africans like me were never afforded this luxury. We could build high walls and electric fences, but instead of keeping the urgent injustices of society without, they served only to make more insistent the claims on the consciences within.

So I renounced my American affair and succumbed to the agreeable consolation of it. I flirted with its Tory tongue-in-cheekness; I read Private Eye, watched Have I Got News for You and had a go at The Times crossword. When I completed it once on a flight back from Paris, I imagined a welcoming committee of dignitaries from Boodle's Gentlemen's Club waiting at the Queen Elizabeth Terminal at Heathrow to slap me heartily on the back.

I mimicked Englishness as successfully as a Boerboel might master the foxtrot. My new passport consummated my right to it. But my infatuation with it lasted only as long as British politics remained a game played by civil servants from the Ministry of Silly Walks.

Then Jacob Rees-Mogg stepped out of his cardboard cut-out caricature and into the world of creepy flesh and cold blood.