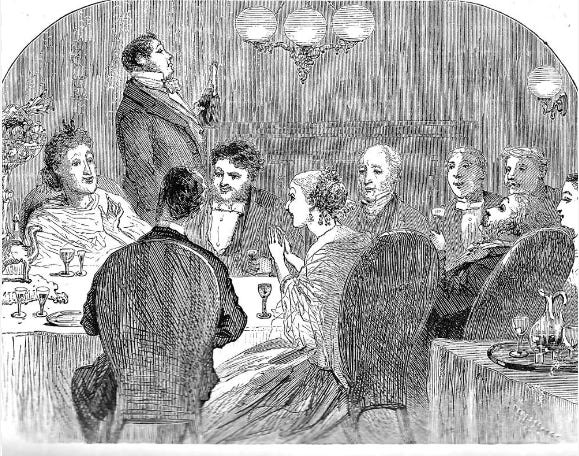

It was somehow understood, as a secret article in the state proprieties of Podsnappery, that nothing must be said about the day.

From Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

I’m taking a break from sex and communism to bring you the latest cricket score: William Wordsworth’s Gentlemen are beating William Blake’s Players by more than 500 innings and some three or four thousand billion runs. The crests of the Players appear to have fallen.

This should come as no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention for the past 229 years.

English cricket fans are thrilled to sing along to Parry and Elgar’s magnificent musical interpretation of Blake’s Jerusalem on the morning of the first day of every Test match at home or abroad. They are less pleased when reality intrudes to remind them that they somehow never got round to building it, i.e., Blake’s Jerusalem. And the few foundations they had laid in more optimistic times had long ago been sold off to the highest foreign bidders.

Which is when they go back to Wordsworth to reassure themselves that imagining God’s City is a lot more satisfying — not to say significantly more economical — than making it more to God’s liking.

In the world of Wordsworth, everything in England was pretty much perfect already. It would be improved only if they could bring back Milton to remind the lower classes of the importance of good manners before they all became French. Or that’s what he kept telling his wealthy sponsors, admirers and patrons in the English establishment.

It is a little publicized and egregiously uncomfortable fact that he confessed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, when the latter visited him at his home in the Lake District in 1833, that he, William Wordsworth, soon to be appointed England’s poet laureate, was fed up to back teeth with the wet and dreary English countryside and was fantasizing secretly, but apparently shamelessly to Waldo, about packing it all in and fucking off to the sunshine, sand and sex of Rio de Janeiro forever. It’s hard not to like him for that.

Perhaps it’s the only thing to like him for. In other respects he was a miserable, miserly, pompous prick of a prig of an English nationalist with the self-awareness of a trout.

You’re not obliged to believe me. Just read Emerson’s account of their meeting in English Traits, the American philosopher-poet’s summing up of his impressions of England on his visits abroad in 1833 and 1847-8. The inspiration, obviously, for mine.

Life is too short, you will say. I agree. So let me cut to the chase.

There are two great schisms in the English-speaking world.

The biggest of them is the Atlantic divide between the English-Anglo view of the obligations of life, and the way it contrasts with its North American Anglo counterpart. The widest of them is the domestic divide in England between the Wordsworthians and the Blakeans.

The Atlantic schism was articulated and defined by the dyspeptically brilliant Thomas Carlyle who put forth the idea that the world's history was nothing more than a collection of biographies belonging to great men, the so-called Great Man theory of political and social change. It is not insignificant that Hitler, in the days before taking his own life in his Berlin bunker in April 1945, was engrossed in Carlyle's biography of Frederick the Great, and wondering, perhaps, how it all went so wrong.

The opposing theory was articulated and defined by Emerson, Carlyle’s great friend and life-long correspondent, who put forward the idea that individual men and women could shape their own destinies by following the truths suggested to them by their very hippy “inner lights”, and hence shape the destiny of Anglo-North America.

In summary, the English-Anglo perspective, which continues to prevail today in the ex-British colonies and all of the Commonwealth, is that your obligation and your bounden duty, as an individual citizen, is to follow your great leader no matter how corrupt or how self-interested his (usually his) aims may be.

The American-Anglo perspective is the polar opposite, i.e., fuck the great man and let me get on with doing what I want to do. (Cf. Emerson’s essay on self-reliance).

These are very broad and sloppy brush-strokes. But time is of the essence.

The most irreconcilable of the two schisms is an English domestic version of the first. We can reduce it, again very crudely and in very broad brushstrokes, to the temperamental, artistic and political divide between Blake and Wordsworth. And most vividly so in their very different views of London, Blake’s in the summer of 1792; Wordsworth’s just ten years later, in 1802.

A lot of smart people have voiced their opinions about the significance of the startlingly contradictory visions that distinguish Blake’s Jerusalem from Wordsworth’s Westminster Bridge. I can add some value to their expert analyses only by claiming to see the differences between them from the perspective of an outsider who came to England as a devout and optimistic Wordsworthian, and left it in disgust as a bitterly pessimistic Blakean.

For sixteen years I too believed the earth had not anything to show more fair than my adopted London. I would drive my smart little black Audi from the south-west suburbs through glittering Knightsbridge to gracious Berkeley Square with Wordsworth’s words competing, and handsomely winning, the battle against Christina Aguilera’s "Come On Over Baby (All I Want Is You)" on the Audi’s radio.

Earth has not any thing to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802 by William Wordsworth

Until 2016 when it occurred to me that a spring morning in Namaqualand could probably give the view from Westminster Bridge a run for its money. So too Paris in the sunshine, or Prague, or the Danube, or Manhattan on a bright September day. So too the Drakensberg in its majestic silence.

The point is that Wordsworth was never writing poetry. He was writing very good advertising copy for his patrons to read to themselves about themselves before dinner.

Now compare Wordsworth’s sublimely polished copy with the first two verses of Blake’s 1792 view of London:

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear…

Look up the rest. It’s disturbing. Which is precisely the difference. Wordsworth was writing to comfort the disturbed. Blake was writing to disturb the comfortable.

This diversion into late eighteenth and early nineteenth century English letters was inspired not only by the hilariously uninspiring scenes in the Long Room at Lord’s on Monday, aka, The Ambush of the Gammons, about which there seemed to be nothing to say that could be more absurd than the already well-documented absurdity of it, but, more pertinently, by the happy happenstance of coming across Zadie Smith’s hilarious reflections on her unhappily sticky English literary traits in the New Yorker yesterday, to wit: On Killing Charles Dickens, The New Yorker, 3rd July, 2023.

And since our brains appear to process everything everywhere all at once, also because, by happenstance again, I had just been putting the finishing touches to the lyrics of a song about Blake’s Jerusalem while Jenin was burning. I will share them with you in due course.

Zadie Smith was, or is, thinking of writing an historical novel. Her problem is that whenever she thinks of history, she thinks of Dickens. I don’t want to spoil it for you but too bad: She ends up having to kill him, bury him in Westminster Abbey, and read his his last rites. Otherwise he and his characters will be haunting her nascent creative thoughts forever. “Dickens was everywhere, like weather,” she writes.

And then, as if she’s been reading this thing of mine, “The English seem to me to be constitutionally mesmerised by the past. Even Middlemarch is a historical novel!”

Sic.

We’ve been her before. Some countries, tribes, families and football teams have usable pasts. Some of them don’t. South Africans has too little history in common for it to be shareable across all our communities. England has so much it can barely live in the present, let alone see through it sufficiently to contemplate the future. Dickens alone is accountable for way more than a fair share of how we view London. The other Victorians thickened the fog of it. The Edwardians made it rhyme for chimney-sweeps and other children.

And then Zadie again, like a dagger to the heart of this apparently unstoppable auto-da-fé of my English roots: “After all, a writer can be deracinated to death…”

Which stopped me, but not in my tracks. Because I was looking at the footage of the kerfuffle in the Long Room and I recognised him immediately.

It was Podsnap, Dickens’s sublime creation of the entitled, xenophobic, red-faced, small-minded, petty, self-satisfied, patronising, smug, jingoistic, upper-middle-class English Brexiteer — those drooped-lipped, double-chinned, overfed and hairless wankers who come to Lord’s to jerk off to a swashbuckling century by a hired Kiwi mercenary as he humiliates, crushes and grinds into the deep green turf of Lord’s the filthy, culture-less scum of kangaroo-buggerers who dare to question the right of Empire to a perpetuity of ever more glittering victories over foreigners who seem incapable of learning their lessons in mute obeisance to their masters.

Then the hurt apparent in their feigned innocence after receiving their polite reprimands: Who, me? — the painfully, pathetically poignant stock and stuff of Empire’s unquestionable chastity.

Me, you say? I just shuffled the papers and signed the note that came from on high. Wasn’t me who pulled the trigger or doused those kids in paraffin or lit the match that turned them into flaming, screaming Catherine wheels with little black legs.

We saw you do it.

I’ll see you in court.

Yes, it was Podsnap himself, the brilliantly representative sample of that species of mind-manacled Englishmen and women who have persuaded themselves that Wordsworth’s view of London from Westminster Bridge was all the evidence they needed to assume Blake’s Jerusalem was an accomplished fact.

Given the current NHS crisis unfolding in England today, the dire state of which institution is plainly the consequence of deliberate Tory under-funding calculated to to accelerate privatization by the same stripe of Tory friends and donors who sucked hundreds of billions out of England’s privatized water, privatized gas, privatized mail, privatized steel and every other sector and utility formerly owned by the state, it’s worth remembering that Clement Attlee’s 1950 manifesto to bring health, affordable housing, transport and all England’s other significant utilities into public ownership was inspired explicitly by Blake’s vision of England as a New Jerusalem. The NHS would be the founding stone of it.

Today is the NHS’s 75th birthday. The NHS created by Nye Bevan, the miner from Wales who Churchill called “a squalid nuisance”, and the Tory papers called a communist AND a fascist.

See also: https://redbrickblog.co.uk/2020/11/building-the-new-jerusalem-how-attlees-government-built-1-million-new-homes/

Our Mutual Friend, written in 1864–1865, would be Dickens’s last book. In my view only it is the worst of his novels and the best of his novels, to paraphrase the man himself. It was slammed by the critics at the time. They were mostly right. The plot is as thin and ludicrous as it turns out to be predictable. Henry James described its characters and their behaviour as "a mere bundle of eccentricities, animated by no principle of nature whatsoever."

It’s a baggy, shapeless. apparently pointless, strange lump of a thing. Dickens is clearly desperate to say something he has never allowed himself to say before. He’s running out of time. He takes risks. He no longer cares to please. That’s where its brilliance lies, in its desperation.

He dismisses structure, plot and character development with a listless disdain. He starts breaking the language and deconstructing the rules of the game. It seems to me that he knows at last that the romance is over. He regurgitates the same old sentimental tropes but his disgust is evident. From the chaos of all of this emerges Podsnap, as if Dickens has finally identified the archetype of the true Dickens fan he’s been writing for all these years. And he’s mortified. Because he understands that it’s always only been about the money and the lack of it - for him and for them. How money makes class and class makes money.

If you read it at all, read it for the conversation at the Veneerings’ dinner table. All the clues are there. You can hear them, feel them and smell them. He is suffocated by the classlessness of precisely that money-grubbing class who constituted his readers, made him famous, and made him rich. He’s been writing for Mr and Mrs Podsnap. He knows it and he owns it.

He has broken himself free of Blake’s mind-forged manacles. And his own.

I phoned the friend of a friend. I crumpled the SADF’s manila missive into a ball and tossed it in the bin. I packed up all my belongings and drove into the night.

Farewell Coriolanus. Onwards to Jeremy Taylor, Cyril and Middlemarch. Via Hlotse.