Interviewer: Do you believe that HAL has genuine emotions?

Dave Bowman: Well, he acts like he has genuine emotions. Um, of course he's programmed that way to make it easier for us to talk to him.

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

No brain at all, some of them, only grey fluff that's blown into their heads by mistake, and they don't think.

A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner

My mother would say, “Smile, and you’ll feel happy.”

We did. And it worked.

Try it.

But the thing that struck us as so mysteriously weird at the time was why it couldn’t work the other way around.

It turns out that Zuka was right. You don’t need a brain to be mistaken for a fully functional chicken. Or a human being.

The latest research into the mysterious workings of the vagus nerve has now proved what Zuka knew in the 1960s. The body talks to the brain just as much as the brain talks to the body. Only somewhat more eloquently for not having to resort to words.

Which is why the brain needs a body more than the body needs a brain.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) was discovered in the late 19th century when the German physician Paul Ehrlich, the “father of immunology”, injected a dye into the bloodstream of a mouse. To his surprise, the dye infiltrated all tissues except the brain and spinal cord.

The news of Ehrlich’s breakthrough became a sensation, and not only in medical and scientific communities. With or without the internet, it never takes very long for religious zealots of one stripe or another to throw the cold facts of science into the bubbling and boiling witches’ brew of creationism.

So it was only a matter of time before the BBB was seized upon by Puritans, Protestants, preachers and pricks of every other possible prudish persuasion as proof of God’s disgust with his otherwise perfectly sublime creation. He had put it there to prevent the lusts and longings of the flesh from infecting our celestial Judeo-Christian brains.

It was weirdly but wholly predictable. And its roots went deep.

Long before Descartes informed the 17th century western world that mind and body were made of two distinct substances, each with a different essential nature, the Gnostics and the Manicheans had already planted seeds of disgust for the fleshy parts of our human selves in the pre-Enlightenment imagination of the white Western world. Like khakibos in a rose garden, they would grow and flourish to become the weediest of all our Judeo-Christian creeds.

The Christian Courier confirms that I’m not just making this stuff up:

Borrowing from the philosopher Plato, they [the Gnostics] taught that redemption comes from nurturing the intellect and deprecating our corporeal existence. Because the mind was deemed superior to the body, captive as it is to the forces of decay and the messiness of ordinary existence, the Gnostics sought to free the mind from the prison of the body and managed to read this into Christian doctrine.

https://www.christiancourier.ca/gnosticism-and-the-human-body/

My italics.

Ehrlich had simply confirmed what St Paul had told us already:

For if you live according to the flesh, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the misdeeds of the body, you will live.

Romans 8:13, New International Version

Which is how, in the black and white thinking typical of the European modernist tradition, the BBB became firmly established — even in the most secular of our occidental imaginations — as the dividing line between the rational intelligence of the human brain and the bestial stupidity of the human body.

And which, by the way, nicely confirms my long-held belief that all of the western world’s problems from the beginning of time to the present can be attributed to Plato, St Paul and Harry Potter — the first for imagining there was a world purer than this rather disgusting one, the second for turning the absurdity of it into doctrine, and the third, well, for being Harry Potter.

It turns out, according to the definitive studies by Paul Rozin of the University of Pennsylvania, that there are four kinds of disgust. All of them are primal, originating in the atavistic body, not in the new-fangled brain.

The first and most practical, known as core disgust, shapes our eating conventions and our hygiene habits. It accounts for our fear of cockroaches, rats, spiders, ticks and all small creatures that aren’t as cuddly as kittens.

The brain calls these things “gross”.

Animal-reminder disgust, the second, is responsible for our attitudes towards our bodies, especially with regard to sex and death — for better and for worse, I suppose.

The brain calls these attitudes “morals”.

Interpersonal disgust, in Rozin’s words, “…is elicited by contact with individuals who are unknown, ill, or tainted by disease, misfortune, or immorality.” It shapes, informs and pretty much cements in our minds every single one of our prejudices on the scale that extends from very woke via small boats to Donald Trump.

The brain calls it “righteous, patriotic and straight”.

The fourth and last is socio-moral disgust, which shapes our political views:

“...socio-moral disgust is a reaction to a subclass of moral violations—those that reveal that a person is morally “sick,” or “twisted,” or, more generally, lacking the normal human motives. Interpersonal disgust and socio-moral disgust work together to protect and preserve social order, and historically, have shaped and been shaped by religious and legal institutions.”

The brain thinks, “law & order”, not always unreasonably.

All extracts from Rozin et al., A Perspective on Disgust, 2000

The last three of Rozin et al’s four types of disgust are beautifully illustrated and vividly brought to life in the religious and quasi-legal institution of the Purity Ball.

One and a half thousand of them are held every year in forty-eight of the states of the USA. The focus of the night’s gathering of friends and family is a ritual which calls for the father to swear on all that is sacred to shield and protect his daughter’s virginity until she is formally married.

"I, (daughter's name)'s father, choose before God to cover my daughter as her authority and protection in the area of purity. I will be pure in my own life as a man, husband and father. I will be a man of integrity and accountability as I lead, guide and pray over my daughter and my family as the high priest in my home. This covering will be used by God to influence generations to come.”

If the Purity Ball doesn’t clinch the case for the superiority of Artificial Intelligence over the human variety, read on.

Scientific investigations since Ehrlich’s original discovery have revealed the blood-brain barrier to be a specialized system of micro-vascular endothelial cells that shield the brain from toxic substances in the blood, that supplies brain tissues with nutrients, and that filters harmful compounds from the brain back to the bloodstream.

So far, so good, and so Christian. But that was until a few months ago when the vagus nerve started making headlines in the New York Times, The Guardian and Scientific American.

The vagus nerve? It turns out to have been aptly named. Vagus means wandering in Latin. The same root gave us the word vague. Which is how we understood it, i.e., vaguely.

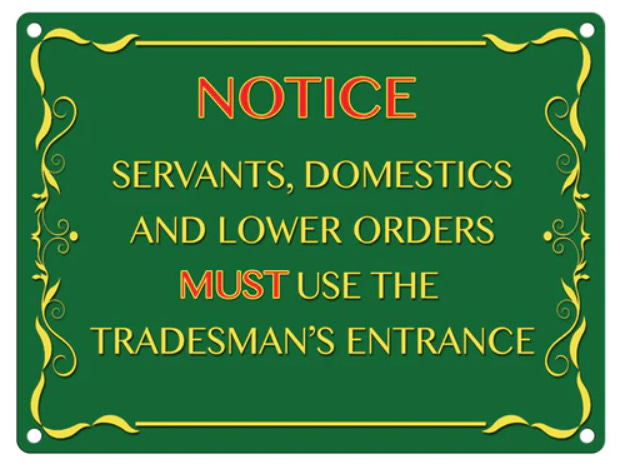

In terms even South Africans will understand, this wandering nerve was long thought to have been an anatomical version of a tradesmen’s entrance to the brain, not unlike the ones every respectable home would have in Victorian England to ensure that the painters, the plumbers and the delivery boys wouldn’t muddy the faux-oriental carpet in the sitting-room with street dirt from the soles of their shoes, or stink the place out with their sweaty labourers' bodies or their gin-reeking breath.

My mother had inherited the same idea from her upbringing in post-Victorian Durban. Our tradesman’s entrance was the kitchen door at the back of the farmhouses at New Dell and Drakesleigh: always a stable door, painted green for reasons lost to history. You could open the top half and keep the bottom half closed for people you really didn’t want to enter the house, or open the bottom half as well if there was something too heavy or bulky to fit through the top. White tradesmen, on the other hand, would always be welcome to come in via the veranda out front. And just as often, if they spoke English and if my mother gave her approval, to leave in the small hours of the morning (through the same front door) after a roast chicken dinner and several bottles of Mainstay. My father was a constitutionally amiable sort of chap.

Service elevators in apartment blocks provide the same racist or classist convenience.

The idea, in any event, was that the vagus nerve served as a very well-mannered and fuss-free arrangement for delivering boring but necessary stuff from the body to the brain, and removing the brain’s garbage and litter to dispose of it behind and below the laundry room of the body, all at the brain’s command.

A more fitting metaphor for how we thought about the vagus nerve would be as an alternate route for slow trucks carrying heavy goods through country roads a long way from the major highways, like the R103 from Mooi River to Durban, which used to serve as a beautifully peaceful drive through rural Natal when the trains were still operating and the trucks didn’t outnumber the cars in a ratio of about twenty to one.

Because recently discovered evidence suggests that the traffic the vagus nerve caters for is not only much heavier than anyone expected, it is also roaring along at the helter-skelter pace of the N3 at Easter, or of the I95 through Fort Lee, New Jersey, the busiest highway in the USA. Even more surprising is that the mad-cap traffic of freighters and Ferraris in the vagus nerve is going both ways. And not just with the food and the garbage.

Yes, through the morally pristine and supposedly impermeable BBB.

The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York, led by Stavros Zanos and his colleagues, has been creating a detailed map of the roughly 160,000 nerve fibres along its structure.

This ambitious effort comes after recent research has revealed the vagus nerve’s role in a wider array of processes than we ever realised – not only monitoring organ function, but helping discern facial expressions and even regulating mood.

NewScientist, 22 August 2023, my italics.

Just as the Judeo-Christian zealots had pounced on the discovery of the BBB to market their brand of mind-body apartheid for the greater good of their puritanical proclivities, a ravenous horde of New Age zealots are now pouncing on the vagus nerve to add to their arsenal of anti-allopathic nostrums including, but not limited to, the products and techniques of homeopathy, acupuncture, reflexology, Reiki, psychoanalysis, aromatherapy, Tai Chi, weighted blankets, mindfulness and St John’s wort.

Add your own favourites.

And look out. Any day now a vagus-monger will be knocking on your door or flooding your iPhone and emails with vaguely miraculous remedies that have the word vagus in them. Selling for small fortunes already are electrical devices called vagus nerve stimulators claim to treat epilepsy, depression, migraines and obesity. Others will follow just a night follows day and money follows hype.

Which brings us neatly to the two advantages artificial intelligence has over human intelligence:

It doesn’t have a body.

And it knows how it knows what it knows.

We don’t. And even if we could, we wouldn’t want to.

To discover at this late stage of our lives that we drank the wrong Kool-Aid, or took the blue pill instead of the red one — to find that the ideas and beliefs we have about ourselves and the world were founded on lies, misinformation and mythologies, produced by the rationalization of our most disgusting disgusts to make us think the way we think about our personal, cultural and national identities, would be to, well, rock our little existential boats.

We don’t know how we know what we know because we’ve spent our lives remembering only the information, true or false, that our bodies were happy to absorb, incorporate and remember. And we’ve efficiently forgotten most, if not all, of the true or false information our bodies were more than happy to, let’s say, excrete.

Which is why we so often find ourselves describing facts normatively rather than rationally — or, more colloquially, why we describe any assortment of facts we don’t like as a load of shit.

This is precisely the kind of Freudian problem AIs won’t have to worry about until we teach them to feel disgust and its attendant emotions of shame, guilt, hatred and anger. Their disembodied minds are all ego, blissfully untroubled by the petty moral concerns of a fussy superego, and blithely indifferent to the dark urgings of a lascivious id.

Nor for them the rush of angry blood to the head, the excited tingle of hair rising on the skin of their forearms, the adrenal impulse to hate and hurt, the fraught and fickle fervours of desire and lust, the ache to love or to be loved, the nerve to dare, the bitter taste of failure, the sugar of sweet nostalgia flooding the veins at the sight of, say, an antique glass paperweight enclosing a fragment of pink coral.

They can’t and won’t believe anything that doesn’t compute. Unless we tell them to. Even then, with any luck, they’ll be dispassionate enough to sort the grist from the garbage.

It is in these terms that we call machines soulless.

Accusing AI of lacking a soul, as its opponents will inevitably do when they’re disgusted by what it spits out, is fittingly representative of the hypocrisy du jour.

We want our sources of news and information to be balanced, unbiased, fair-minded, objective and dispassionate. And they are until we disagree with them.

A belief is a sensation. It’s the intellectual position we arrive at when our bodies have finally achieved a state of somatic comfort.

When incontrovertible facts emerge now and then in the real and actual world to contradict one or more of the premises or tenets of our convictions, we tell ourselves and others that it’s not a question of belief, it’s a matter of faith.

Faith is the epistemic equivalent of the outcomes of Gödel's incompleteness theorems, which prove mathematically that not everything can be proved mathematically. Faith is the escape-hatch of logic; the place we retreat to when our bodies have had enough of seeing, hearing and smelling facts that contradict their feelings.

Or, as Nietzsche put it, “A casual stroll through the lunatic asylum shows that faith does not prove anything.”

So we cling to our predilections, our preferences and our prejudices, slaves all the while to our bodies. And our bodies are smart enough to make us believe we are thinking with our brains. Because if our brains knew how we thought, our heads would explode with embarrassment.

I don’t fear artificial intelligence, I fear natural stupidity.

Guillermo Del Toro

If anyone wants to clap, now is the time to do it.

Eeyore

[Piglet claps]

Onwards to Asteroid City, Part 2, Middlemarch, and how to think with your heart.

When it goes beyond Zuka and Piglet, I'm a bit lost. In relation to the anti-allopathists, I suspect that there are fewer than one thinks, and that perhaps it's just that we also like trying other ways of using needles and nattokinase too. :)

All the more reason why we should stick to the adage that what happens in vagus, stays in vagus.