“A functioning, robust democracy requires a healthy, educated, participatory followership, and an educated, morally grounded leadership.”

Chinua Achebe - Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic

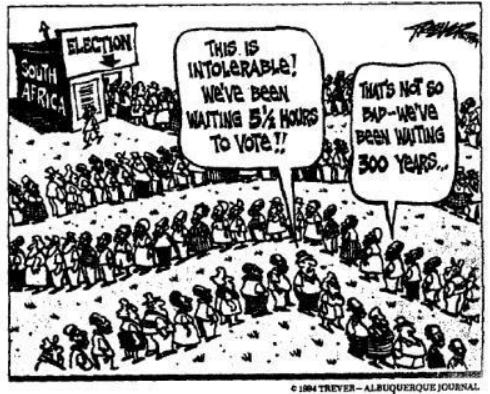

I had very good reasons believe in democracy. Thirty years ago I saw it work at its miraculous best when 19,726,579 people, the vast majority of whom had been disenfranchised since 1948, and whose kith and kin had been disenfranchised since the days of Cecil John Rhodes, turned out on the 26th, 27th, 28th and 29th April 1994 to consign apartheid to the dustbin of history.

I was there, I was part of it, I lived every moment of it.

As Creative Director of the official voter education campaign that helped to make the election as peaceful, patient and proper as it turned out to be, I’m still immensely proud to have played a small part in its success. Yes, of course. It’s just, well…

My copywriters at JWT were the deeply-missed Eugene Strauss and the extraordinary Nondwe Dazana. My art director was the wonderful Sue Edelstein. My producers were Mandy Milsap and the sorely-missed Grant Shakoane. The Account Director was Linda Radford, quoted in the New York Times article below. Our Managing Director was Peter Sham.

I’ve probably forgotten a bunch of others. Apologies. Please let me know if you were there.

I can’t remember why they appointed us — they being IFEE, the Independent Forum for Electoral Education, a motley crew of recidivists, racists, radicals and revolutionaries drawn from every shade and stripe of the very splintered South African political spectrum, led by the remarkable Barry Gilder, the rock-star of righteous anger.

I suspect it was because they could sense how desperate we were to work on something other than Mentadent P, Rice Krispies and Kraft’s latest margarine.

It’s tempting, in the golden sunset of retrospect, to romanticize the momentous achievement of it all. The photographs of those endless queues waiting to vote for freedom still sing with the sentiments of the time. But they’re tinged with the nostalgia of broken hearts, like the wedding pictures of a perfect couple destined, we now know, to end in mutual tears.

And since I have written about it elsewhere, often and usually way too optimistically, I will leave it to the aptly named, lyrically-breathless and sadly-departed Francis X. Clines of the New York Times, writing just a few days before the election, to recapture the spirit and intent of what we, IFEE and others had been doing in the years, months and weeks before those four fateful days.

There was a pastoral sweetness in the room as the once-fantastic idea of voting freely in South Africa was explained at the Soweto Home for the Aged to 50 black people who had suffered the longest across decades of racist white oligarchy.

"You have lived long and can give us a great legacy," Zweli Nkosi, a voting organizer, explained amid the grand metamorphosis now sweeping this nation toward the approaching election. "Mark your stamp on life. Give us your final gift: Vote."

The room of old people, poised as if at a bonus rite of passage, responded with a burst of applause and cheers, some putting aside cane and crutch.

"I'm voting for the return of my country," declared 77-year-old Jerry Buthelezi, lean-faced and content under a big brown fedora. "That's important. That's a beautiful thing."

In South African cities, the message is carried in thumping rap lyrics, in a special voters' soap opera and "Make Your Mark" election quiz shows on TV, and in euphoric liberation ads worthy of the glossy yearnings in Ronald Reagan's "morning again in America" commercials. One shows a bright huge voting-X pattern of a throng of multi-hued humans moving lushly across a green and promising national landscape.

It is a ubiquitous message, from programmed cassettes on black workers' jitney vans to the fading primacy of the white Afrikaner-run television channel where a Wagnerian singer booms clunky two-step jingles about a future that will somehow prove grand for all. "We're gonna have a ball!" she croons and sways and grins to the tune of "After the Ball Is Over."

The message is not monolithic, for the voter education drive is directed at all sorts of problems. One pitch, emphasizing the secrecy of the ballot, is intended to undercut husbands' attempts in traditional tribal areas to dictate their wives' choice. Other messages warn against scheming tribal chiefs who are demanding patronage tithes as the price of franchise, and against white overseers who are confiscating their black farm workers' identity cards to hinder voting.

Cautions toward fairness rain down endlessly in the media. There are the sitcom family morality tales of the popular comic actor, Joe Mafela, spokesman for the Chicken Licken restaurants. There are the theater tableaux of Black Sash, the highly respected women's protest group. All the hurried innovations of democracy's mechanics -- from ultra-violet hand dye at the ballot box to an 18-party potpourri of options on the first of two paper ballots -- are being explained to the 22 million eligible voters, especially the black majority long denied a fair and thoughtful franchise. A Rite of Transformation.

But the overall point of the voter education drive, costing somewhere beyond $30 million, is that the vote is not merely about a leadership choice, but about a people's passage to a higher phase of democracy and national definition. "Heal Our Land" is the slogan under an X of crossed Band-Aids. It is an imprimatur on liberation. The likely result, the choice of Nelson Mandela as national leader, is well known, but not the volume of turnout in ratifying a transformed nation.

"It is a grand, purificatory moment in which the nation is to pass through a membrane of history from darkness to a sunlit upland," wrote Simon Barber in Business Day, relishing with sarcasm the TV commercial blitz, including one showing a patriarchal old man walking miles to vote, clutching the hand of his grandchild. A Long Walk to Freedom.

In fact, Mr. Wolpe saw just such a tough old man climb three hours down from his mountain home to join a hamlet crowd of 250 for a practice vote at the elections van. South Africa is in just such a state, trembling somewhere between the wondrous reality of the first-time voter facing the fullest choice, and the Utopian dreams of the modern media's motivation arts.

"This was real heart-and-soul stuff," said Linda Radford, account director on some of the most lyrical ads for the local J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. "The task was daunting," she said, noting professional crews were more integrated as they filmed idealized ethnic portrayals that would have been treasonous in the recent past.

Barry Gilder, one of the chief creative executives of the drive as communications chief of the Matla Trust, can talk in detail of fine tuning the message in such critical areas as radio, the most effective medium for reaching the black poor majority in rural and small-town areas. But he feels that foremost is the campaign's overall spiritual dimension.

"It's like a kind of catharsis," he said, "even for white people, who want an end to the uncertainties and the fear, the guilt and the anxieties."

Matla Trust, a nonprofit organization, was one of a score of groups in the Independent Forum for Electoral Education that began preparing for the day of a free vote well before the Government's moves to dismantle apartheid put that on the horizon four years ago.

The campaign now includes hundreds of organizations operating through the forum, and through the Democracy Education Broadcast Initiative of media professionals, the Business Election Fund of private entrepreneurs, and the Independent Electoral Commission, the interim Government body which has taken an ever firmer hand to avoid postponement of the elections in the face of violence and resistance in KwaZulu, the homeland created under apartheid for the Zulu people.

Even with all the problems and confusion and protest violence in some areas, campaign directors hope for a turnout of up to 85 percent. Blacks are the most enthusiastic, while the racially frayed nation's mixed-race and Asian minorities are most ambivalent, reflecting a fear that they will remain in a political limbo, second to black majority power as they have been a secondary buffer for the white regime.

Countless foreigners are arriving to help get out the vote and monitor the election. Craig Charney, a Yale political scientist, has been here for several years, working lately as a broadcast news polling expert.

"It's an extraordinary thing to see millions of people around the country put slips into a box and see their government change as a result, without tanks in the streets," he said, looking beyond the demographics. "South Africa is going to become not a Western style democracy but a wobbly, imperfect third-world democracy. But it is a vast improvement over what came before." Some Find Fault.

In democratic fashion, there are numerous complaints. Some white political leaders charge the education drive favors the black majority. Other people feel too much faith has been placed on entertaining TV ads and not enough on the face-to-face approach favored by Mr. Nkosi in visiting the Soweto old folks.

"What's a political party?" he asked, and "Mandela!" was shouted in reply by one old man, grinning gap-toothed.

Jabu Mohlouwa, a social worker, smiled at the scene. "People think this election will put honey on their plates, but they're wrong," she said. "They think Mandela is a magician. He's not."

But her elderly charges plunged ahead into the future, intoning his name and asking more questions about how to vote free.

Francis X Clines, New York Times, 12th April, 1994

My breathless italics.

But that was the hype and the hope. Reality was something else.

The closer it got, the more invested we became. For IFEE and the team at JWT it was no longer an advertising campaign — it was the mission of our lives: past, present and future. We weren’t making pamphlets, radio spots or TV commercials any more. We were making history.

Yes, I know.

There were hundreds of issues to address, thousands of fears to assuage, millions of people to persuade to do the right thing at the right time. There were the principles, and then there were the practicalities.

Without a registration record of every eligible voter, the technique we used was to make every voter dip their thumb in purple dye as proof they had voted. It couldn’t be washed off for the four days it took to complete the election.

But how to address the illiterate, the young, the suspicious, the angry and the feeble? How to get them, one and all, to embrace the idea of democracy when the great democracies of the world had been complicit for so long in giving overt or tacit support to the apartheid state?

The days themselves are a blur. All I remember is getting the agency team together with the IFEE people in hotel bar somewhere in downtown Joburg when it was over, drinking the night away and pressing our purple thumbs together in hallelujahs of ecstasy — black, white, coloured, Asian, weird and wonderful in a purple haze of pride.

For a brief moment in the long history of man’s relentless inhumanity to all other living creatures, it felt as if the whole planet had paused in wonder.

Democracy in South Africa worked until the purple dye wore off. It worked for as long as it took the ANC government to realise you could still call yourself a democracy without Chinua Achebe’s “healthy, educated, participatory followership” or, for that matter, “an educated, morally grounded leadership”.

In which respect the ANC government was simply following the example of those great democracies who learned long ago to hide the absence of Achebe’s other essential ingredients for a fair and flourishing polity behind a paywall of calumny and cant.

If all the many vital elections held around the world in 2024 aren’t going to lead us to a post-truth version of Orwell’s 1984, the need for constant protest that demands and gets accountability from our democratically chosen governments in the plunder-and-pillage interregnum between one election and the next has become more vital than ever.

In South Africa and every other self-described democracy.

Perhaps the most important lesson to reflect on is that elections, though important, are just one part of a functioning democracy. Indeed, over the last 30 years, we have learned that in a democratic society, real results depend on people holding their leaders accountable through protest and community organising, not by voting alone.

Safia Khan & Tarryn Booysen

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/4/27/south-africas-post-apartheid-democracy-is-sustained-by-protest

Thank you, Gordon.

You have captured the essence of that "golden time" and something of the deep disillusionment and sense of betrayal felt by many of us 30 years on. However I still have hope for our "wobbly" democracy and faith that the majority of our people are still pursuing the dream.

Fiona and I send you our best wishes and appreciation for your skill with words.