A world of total epistemic warfare is a world in which the past will become dramatically less usable.

Ben Alpers, Society for US Intellectual History, June 17, 2013

Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

The Party slogan in George Orwell’s 1984

Resorting to Orwell to describe how and why we came to find ourselves here, lost in an epistemic wilderness in which it has become impossible to write about propaganda without being accused of writing propaganda, has become as tiresome as it is tiring. Which, in an Orwellian kind of way, is probably the point.

Orwell was an ardent and committed socialist. When the political right succeeded in turning Animal Farm into an anti-leftist fairy tale, irony was exhausted.

I wouldn’t have been thinking about this if I hadn’t chanced upon a brilliant article by one Masha Gessen in the New Yorker of 10th June, 2018, titled, “How George Orwell Predicted the Challenge of Writing Today”.

Nor would I have read it with such interest if I hadn’t recently been wondering, admittedly in a vague, speculative and lazily Leavis-like fashion, why so pitifully few great novels had been written in English by a born and bred English person since, I dunno, Middlemarch in 1871.

And I wouldn’t have dared to resort to Orwell if 1984 hadn’t already happened in South Africa in 1977, and to me, personally, in 1975.

I should probably start there.

Like Orwell himself (aka Eric Blair) at the BBC, and like Winston Smith, Orwell’s protagonist in 1984, I learned the inside and out of propaganda by writing it.

Winston Smith wrote the news for the Ministry of Truth when Total War was the only way of maintaining the Total Peace of Oceania. I wrote the news for the SABC from January 1975 to January 1978 when South Africa was a shining beacon of democracy on the African continent, when our best friends in the world were the most brutal dictators in the world, and when our next-best friends were those other shining beacons of democracy who were happy to turn a blind eye to the iniquities of apartheid by persuading themselves and each other that our stubborn refusal to give the vote to people who weren’t strictly white was a truly ingenious way of preventing the global spread of communism, socialism and baby-eating.

I mention the dates because —as luck, fate, destiny or the obligation of nature to assign every particle/wave to somewhere would have it — the period turned out to be significant, propaganda-wise.

South Africa’s first experimental television broadcasts began on 5 May 1975. The nationwide service began on 5 January 1976. Five months later the SABC would broadcast selected scenes of the Soweto uprising to the country and the world, some of them mine. The nationwide insurrections that followed would lead P.W. Botha, Minister of Defence at the time, to formulate his plan for Total Onslaught in 1977:

"The resolution of the conflict in the times in which we now live demands inter-dependent and co-coordinated action in all fields: military, psychological, economic, political, sociological, technological, diplomatic, ideological, cultural, etcetera. We are today involved in a war whether we like it or not."

So I learned my doublethink early, and employed it to make a moderately successful career for myself as an advertising copywriter.

I had no illusions about what I was doing. But the cynicism of selling cheap bars of soap to desperate housewives in Khayelitsha, Kenya and Kyrgyzstan on the premise that it was the must-have luxury item of the world’s most glamorous women nevertheless felt by some degrees less cynical than selling the benefits of apartheid to the 193 sovereign states of the United Nations.

It was apparent to me at the time that the skills I had learned while writing the news were seamlessly transferable to advertising, most pertinently among them a highly selective approach to the truth or, as George Orwell called it, “organized lying".

In most countries in the world, commercial brands are prevented from lying as much as they would like to by regulators with strict codes of conduct. These will usually allow for some artistic licence. Hyperbole, for example, is permissible within limits; exaggeration is not. Fabrication is allowed in the form of fantasy if it is fantastic enough. Falsification might be allowed for comic effect. But commercial purveyors of the kinds of lies of fact that slip so slickly and soapily off the tongues of unscrupulous politicians would, in the realm of advertising, generally be outed and punished, sometimes financially, invariably reputationally.

Codes of conduct such as these work well enough in a world where it is in the interest of all parties to abide by the rules of the game, where the truth matters enough to the community of all players to create and fund a body of independent third-party regulators to guard the guards, and to agree to conform to their judgements. VAR springs parochially to mind.

Looking at it now, twenty-five years since I last wrote a thrilling headline for a toilet cleaner and just a few days after the mind-numbingly lavish exercise in mass hypnosis that was the coronation of King Charles III, it is disturbingly self-evident that, despite the undoubtedly sincere efforts of the United Nations and its associated agencies, the world of geo-politics is a distressingly long way from refereeing the referees of history, folded and unfolding.

There are a dozen or more types of lies. The least egregious are simple errors of truth or those misinterpretations of the truth that are either lost in translation or passed on in all innocence from an untruthful source.

There are white lies and bold-faced lies. There are lies of exaggeration, lies of denial, and the pathological lies of people who just can’t help lying. There are lies of outright falsification and, as we discovered after Donald Trump’s election triumph in 2016, there are alternative facts. Thanks largely to Trump, to Boris Johnson, and to their veracity-averse counterparts around the globe, these have now become the staple of everyday political discourse, as ugly as acne when the make-up wears thin, but just as natural.

We have learned in the last seven or eight years to take the utterances of world leaders and global experts with large quantities of salt. With enough time, effort, logic, patience and sodium chloride we might, if we cared to bother, track down the unembellished truth these kinds of lies were designed to distort — but only, and increasingly rarely, if the historical evidence upon which they were based hadn’t been tampered with in advance of the lie.

Winston Smith’s job at the Ministry of Truth, and mine at the SABC, was to do exactly that: to control the future by rewriting the past to justify the government’s policies and actions in the present.

As effective as they are, it would take a tidal wave of expensive thirty-second television commercials to rewrite the history of, say, thalidomide. Not so if you owned a news channel broadcasting every minute of every hour of every day of every year to seventy-four million people in two hundred countries.

In this not entirely hypothetical case, unscrupulous parties could select their weapons of mass instruction from an encyclopaedic armamentarium of mendacity to encourage, nudge or cajole their unsuspecting audiences down epistemic paths not entirely of their choosing.

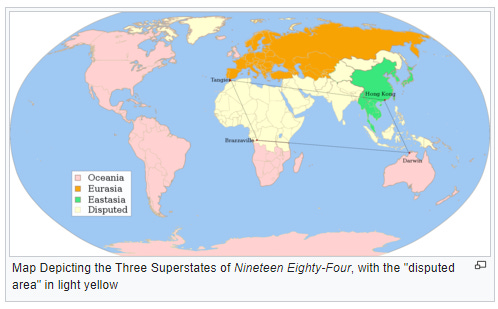

With the appropriate guidance and a nuanced approach to history, the people of Oceania could, for example, be persuaded to believe that the fabulous wealth and treasure of the aristocracy of Oceania, among which the fabulously valuable jewels in the crown of their recently anointed titular monarch were mere trinkets by comparison, was just reward for the universally celebrated success of The Great Civilizing Project of The Empire of Oceania which had freed billions of the Citizens of Wider Oceania from their bondage of poverty and ignorance by instructing them so thoroughly and generously in the values of Liberal Democracy and the Free Market that they would no longer have to eat their babies like the Communists did.

But also, by the way and furthermore, to be aware that the rumours being spread by malicious parties from Eurasia and Eastasia to the effect that Oceania had killed or deliberately starved to death more than a hundred million people on its way to acquiring its glorious pre-eminence in the present day were part of a monstrous campaign of disinformation aimed at undermining the very liberties and values of free speech and democracy that Oceania had striven so courageously, and at the cost of so much blood and treasure, to bring to the very people who were now using it to undermine those very same precious values, etc. They could look it up.

Seldom will sophisticated liars of this stripe resort to the simple fib. Nor do they need to.

Far more pernicious and effective than outright untruths — because they cannot be fact-checked for their veracity in the past or the present — are lies of omission, lies of minimization, and the bait-and-switch technique of distracting our attention from the problem at hand by pointing us to a worse but similar problem elsewhere.

In these three cases, to put it in Rumsfeldian terms, advertisers, broadcasters and unscrupulous politicians know that we don’t know what we don’t know. Into this epistemic vacuum it is easy enough for them to insert a truth or an apparent truth that has the effect of satisfying our need for an explanation, an idea or a point of view we weren't aware we were seeking.

It’s not as complicated as it sounds. We use distraction, minimization and omission both deliberately and unthinkingly in our everyday conversations. Taken together they are the product and purpose of dissembling, that sadly underemployed but deliciously appropriate word for the concealing of our true motives, feelings and beliefs. With its roots in the Latin for disguise, dissembling is what we often do quite naturally to smooth the conversational way, to avoid unpleasantness, to soften the blow, to sweeten the sour, and, above all, to be polite. Or to appear to be.

Distraction, minimization and omission are fundamental to behavioural economics. Magicians use them all the time. So do advertisers, fraudsters, con-artists and most skilfully because it comes to them so naturally, a certain elevated class of English people fabled around the world for the politeness of their disingenuousness. They are born to the manner of it. And the manor of it. Dissembling for the sake of politeness is the sweet elixir they imbibe in their postnatal silver spoons.

They seldom lie to deceive. They do it, as my mother did and as I learned to do in turn, because they tend to regard the uninvited honesty of saying what you actually mean as, well, rather rude — in rather poor taste, as rather blunt, as rather impertinent, as somewhat uncalled-for, as just a touch unnecessary. Their politeness is as charming as it is disarming. It’s delightfully self-deprecating, usually amusing, and occasionally entertaining.

Just as often it can be neurotically, even pathologically, insincere. Boris Johnson, in other words.

Politeness is also the most velvety of all velvet gloves.

The SABC of the 1970s was the colonial step-child of the BBC. Even in those days, long before social media might have found us out, we never lied by deliberate fabrication or falsification. But we were masters at dissembling.

The blue plastic folder we had to read and obey from the minute we stepped into the building to start our morning or evening shifts served as an explicit guide to who or what was to be omitted, minimised or distracted from for the next twenty-four hours, and sometimes forever.

Mandela’s name, for example, could not be breathed. As far as our audiences were concerned he didn’t exist, had never existed, and could and would never come into existence. He was one of several hundred individuals, along with any number of organisations, whose actual living presence could never be acknowledged by mentioning them on the air. That would be, as the saying goes, to give them air.

When anti-apartheid sanctions began to bite in this or that sector of the economy we trivialised them as inconsequential in relation to other sectors that were booming despite them. Razor-wire comes to mind.

If there were riots in our streets we were instructed not only to ignore them but to find sound-bites or sensational footage of angrier, louder and more violent riots happening in Lusaka, Buenos Aires or Paris. Preferably Paris.

It would be surprising then if our Step-Aunty Beeb, these days apparently in thrall to the nonpareils of the English establishment, could entirely avoid an occasional dabble in the fine art of dissimulation we inherited from her. Not to put too fine a point on it, as they might say.

I grew to be as suspicious as I am regarding the intentions of television news not only because I worked for one of the most mendacious broadcasters in the world outside of North Korea but, more importantly it seems in retrospect, because my generation of South Africans, born in the early 1950s, caught our first glimpse of it in 1975 when we were in our early twenties.

It was alien to us, and we saw it as alien, we thought of it as alien, and we studied its behaviour, its manner and its speech the way you would search for the signs and nature of the intelligence, the motives and the intentions of a green-skinned creature with a single, very large multi-coloured, constantly flickering eye instead of a face if one such critter happened to appear unexpectedly on your kitchen counter next to the toaster on a bright Sunday morning in, say, Westdene, Johannesburg, in the years before the test-pattern became the most hauntingly familiar graphic of your lived experience. And then to discover, somewhat frustratingly, that it was entirely oblivious to your words, questions, opinions and screams.

Television had been banned by the apartheid state on the basis that it was the informational equivalent, in the words of Prime Minister H.F. Verwoerd, of “...atomic bombs and poison gas.”

Dr Albert Hertzog, Minister for Posts and Telegraphs from 1958 to 1968, swore that television would come to South Africa “...over my dead body”, denouncing it as “...only a miniature bioscope which is being carried into the house and over which parents have no control. It’s the devil's own box for disseminating communism and immorality."

He also argued that "South Africa would have to import films showing race mixing; and advertising would make [non-white] Africans dissatisfied with their lot."

Yes, since they were so clearly satisfied with the lot allotted to them by apartheid..

South Africa was one of a handful of countries on Planet Earth unable to watch Neil Armstrong setting foot on the Moon in 1969. We listened to the crackling voices of Houston and Armstrong on a transistor radio on the front lawn of Drakesleigh, staring up in awe, hope, fear and wonder at the Milky Way glittering like a million jewels in the moonless night .

Why? What were we expecting to see? Someone, probably Bruce, said, “The Martians aren’t going to like this.”

I was old enough to laugh. And young enough to imagine a fleet of red starships appearing over the black silhouette of the Drakensberg and speeding our way with maliciously nuclear intent.

After the event, in response to public demand, the government arranged limited viewings of the landing where selected guests were able to watch recorded footage for 15 minutes.

So my first view of television, at the age of twenty-three, was from the inside, not the outside — as a writer and producer of it, not a viewer of it. Which strikes me now as the equivalent of seeing the world for the first time not as a baby, but as an obstetrician delivering one.

We had no idea what we were doing or how to go about doing it. At Broadcast House in Commissioner Street we had grown accustomed to the freedom and latitude of not having to illustrate our words or substantiate them with pictures, let alone moving pictures. Radio allowed us to say whatever we liked and we did, admittedly within the claustrophobic guidelines of the propaganda protocol for the day. Now, in the absence of YouTube, we would have go out there and shoot them ourselves.

The problem became blindingly obvious on day one. No matter where you pointed the camera, what you saw in full-colour moving pictures was the unedited reality of daily life in one of the most shamelessly bigoted, aberrant and iniquitous societies in the known world.

There was nothing you could film that didn’t show it. The whites had blue swimming pools in gracious green gardens. The so-called non-whites lived in mud huts or corrugated iron shacks without electricity or running water, or were in crowded into all-black commuter trains on their way to work in the white-owned goldmines or to work in the home of white people with blue swimming pools in gracious green gardens. The city streets were white by night, courtesy of the draconian curfew that obliged blacks to get out of them before sunset unless they had permits to prove they were allowed to wash the dishes in all-white restaurants or sweep up after the crowds had exited their all-white cinemas, discos or nightclubs.

The South African Defence Force and the South African Police used a Byzantine array of laws, an army of state-funded surveillance agents of every colour and stripe, and old-fashioned brute force to ensure that peace and harmony prevailed. The Broederbond, literally the band of brothers, was our Big Brother. Look it up.

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949, and the Immorality amendment Act, 1950, had given us the Love Police and the Sex Police. We would be the Thought Police, studiously determining what South Africans could think about and what they couldn’t think about, but now in high-definition PAL at 25 frames a second.

Herzog had feared that “the devil’s box” would awaken the South African population, both black and white, from the blissful sleep of their ignorance, arousing strange and dangerous aspirations and passions that would have us questioning whether they could ever be fulfilled or satisfied within the walls of the Calvinist prison that was the apartheid state. He would sadly, even tragically, be proven wrong.

Television, like the news, lies by default. What it chooses to show and what it chooses to say is precisely that — a choice. Which by default is always a choice of what not to show and what not to say.

The difference between seeing reality and seeing the same reality on TV is the difference between noticing something yourself and having someone else — a tour guide for instance — telling you what to notice. TV is the tour guide of life. Whatever it shows you must be important. Whatever it doesn’t show you can safely and happily be ignored. That’s the message of the medium.

Through the lens of this delusion, the introduction of television to South Africa had precisely the opposite of the effects Herzog had feared. In pictures that amplified the positives, diminished the negatives and ignored those negatives that couldn’t be diminished, it said in thousands more words than any propagandist could dream of that we lived in a Shangri-La of braaivleis, rugby and sunny skies, as an early and (now infamously) famous commercial for Chevrolet would put it.

TV sanctified the status quo by making us proud to be who we were and happy to be where we were. It legitimised apartheid by showing us how natural, peaceful and normal it was in the real world. What it didn’t show was everything we had anyway learned over time to turn our eyes away from.

And any reservations we may have had about filming the everyday reality of the divide between black and white for all the world to see in technicolour were soon assuaged when we learned that despite their best efforts the commercial managers of the SABC had yet to find a single international buyer for our news footage outside of Paraguay and Taiwan.

So no one we cared about would ever get to see it, and our fellow South Africans would in any event see only what they saw every day, the white ones courtesy of the all-white channel about all-white affairs alternating daily between Afrikaans and English, and the black ones courtesy of the all-black channel about all-black affairs alternating daily between the most spoken Nguni and Sotho languages at a broadcast frequency appropriately distanced from the frequency of the white channel. Of course.

The net effect was paradoxically ridiculous, absurd, anachronistic, bizarre and extraordinary. You had to live in it to comprehend the living lunacy of it.

Actually, no. Living in it was the worst possible place to comprehend it. We didn’t know half of it because the other half lived somewhere else. Everything that could be divided was perfectly divided, not in number but in principle. The land, the wealth, the health, the schools, the universities, the languages, the trains, the privileges, the labour, the colour of your collar, the services, the utilities and now, thanks to television, the way you saw the world.

Apartheid built a white heaven atop a black hell. The separation was immaculate. TV consecrated it. I am constrained from describing every last detail of the Manichean perfection of it only by the guilt of my nostalgia.

Because when I think about those enthrallingly innocent days of my young adulthood a decade before 1984, I can’t help thinking it probably isn’t very different from the way Winston Smith thinks about the gratuitous beauty of his treasured glass paperweight of pink and blue coral in 1984, made at the puzzling time before everything had to be made for a purpose. Including every thought and every word.

Onwards to Masha Gessen’s “How George Orwell Predicted the Challenge of Writing Today”.

And to Middlemarch…

I am mind-blown. You paint the picture of a reality absolutely unknown for us Mexicans. I remember the news back in the 70s... It mentioned that South Africans were simply ‘evil’. Thank you for the nuance. Cheers!

Bravo Gordon. Spot on.